Electron microscopy of soft materials: non-invasive nanoscale imaging

A new non-invasive nanoscale imaging technique going by the acronym CLAIRE is enabling the observation of the dynamics of interactions between nanosized components even in soft materials.

Soft matter encompasses a broad swath of materials, including liquids, polymers, gels, foam and - most importantly - biomolecules. At the heart of soft materials, governing their overall properties and capabilities, are the interactions of nanosized components. Observing the dynamics behind these interactions is critical to understanding key biological processes, such as protein crystallisation and metabolism, and could help accelerate the development of important new technologies, such as artificial photosynthesis or high-efficiency photovoltaic cells. Observing these dynamics at sufficient resolution has been a major challenge, but this challenge is now being met with the non-invasive nanoscale imaging technique CLAIRE (cathodoluminescence activated imaging by resonant energy transfer).

Invented by researchers with the US Department of Energy Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of California Berkeley, CLAIRE extends the incredible resolution of electron microscopy to the dynamic imaging of soft matter.

“Traditional electron microscopy damages soft materials and has therefore mainly been used to provide topographical or compositional information about robust inorganic solids or fixed sections of biological specimens,” said chemist Naomi Ginsberg, who leads CLAIRE’s development. “CLAIRE allows us to convert electron microscopy into a new non-invasive imaging modality for studying soft materials and providing spectrally specific information about them on the nanoscale.”

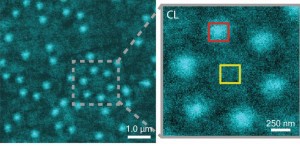

Ginsberg and her research group recently demonstrated CLAIRE’s imaging capabilities by applying the technique to aluminium nanostructures and polymer films that could not have been directly imaged with electron microscopy.

“What microscopic defects in molecular solids give rise to their functional optical and electronic properties? By what potentially controllable process do such solids form from their individual microscopic components, initially in the solution phase? The answers require observing the dynamics of electronic excitations or of molecules themselves as they explore spatially heterogeneous landscapes in condensed phase systems,” Ginsberg said.

“In our demonstration, we obtained optical images of aluminium nanostructures with 46 nm resolution, then validated the non-invasiveness of CLAIRE by imaging a conjugated polymer film. The high resolution, speed and non-invasiveness we demonstrated with CLAIRE positions us to transform our current understanding of key biomolecular interactions.”

The CLAIRE imaging chip consists of a YAlO3:Ce scintillator film supported by LaAlO3 and SrTiO3 buffer layers and a Si frame. Al nanostructures embedded in SiO2 are positioned below and directly against the scintillator film. ProTEK B3 serves as a protective layer for etching.

CLAIRE works by essentially combining the best attributes of optical and scanning electron microscopy into a single imaging platform. Scanning electron microscopes use beams of electrons rather than light for illumination and magnification. With much shorter wavelengths than photons of visible light, electron beams can be used to observe objects hundreds of times smaller than those that can be resolved with an optical microscope. However, these electron beams destroy most forms of soft matter and are incapable of spectrally specific molecular excitation.

Ginsberg and her colleagues get around these problems by employing a process called ‘cathodoluminescence’, in which an ultrathin scintillating film, about 20 nm thick, composed of cerium-doped yttrium aluminium perovskite, is inserted between the electron beam and the sample. When the scintillating film is excited by a low-energy electron beam (about 1 KeV), it emits energy that is transferred to the sample, causing the sample to radiate. This luminescence is recorded and correlated to the electron beam position to form an image that is not restricted by the optical diffraction limit.

Developing the scintillating film and integrating it into a microchip imaging device was an enormous undertaking, Ginsberg said, and she credits the “talent and dedication” of her research group for the success. She also gives much credit to the staff and capabilities of the Molecular Foundry, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, where the CLAIRE imaging demonstration was carried out.

“The Molecular Foundry truly enabled CLAIRE imaging to come to life,” she said. “We collaborated with staff scientists there to design and install a high-efficiency light collection apparatus in one of the Foundry’s scanning electron microscopes and their advice and input were fantastic. That we can work with Foundry scientists to modify the instrumentation and enhance its capabilities not only for our own experiments but also for other users is unique.”

While there is still more work to do to make CLAIRE widely accessible, Ginsberg and her group are moving forward with further refinements for several specific applications.

“We’re interested in non-invasively imaging soft functional materials like the active layers in solar cells and light-emitting devices,” she said. “It is especially true in organics and organic/inorganic hybrids that the morphology of these materials is complex and requires nanoscale resolution to correlate morphological features to functions.”

Ginsberg and her group are also working on the creation of liquid cells for observing biomolecular interactions under physiological conditions. Since electron microscopes can only operate in a high vacuum, as molecules in the air disrupt the electron beam, and since liquids evaporate in high vacuum, aqueous samples must either be freeze-dried or hermetically sealed in special cells.

“We need liquid cells for CLAIRE to study the dynamic organisation of light-harvesting proteins in photosynthetic membranes,” Ginsberg said. “We should also be able to perform other studies in membrane biophysics to see how molecules diffuse in complex environments, and we’d like to be able to study molecular recognition at the single molecule level.”

In addition, Ginsberg and her group will be using CLAIRE to study the dynamics of nanoscale systems for soft materials in general.

“We would love to be able to observe crystallisation processes or to watch a material made of nanoscale components anneal or undergo a phase transition,” she said. “We would also love to be able to watch the electric double layer at a charged surface as it evolves, as this phenomenon is crucial to battery science.”

Revealed: the complex composition of Sydney's beach blobs

Scientists have made significant progress in understanding the composition of the mysterious...

Sensitive gas measurement with a new spectroscopy technique

'Free-form dual-comb spectroscopy' offers a faster, more flexible and more sensitive way...

The chemistry of Sydney's 'tar balls' explained

The arrival of hundreds of tar balls — dark, spherical, sticky blobs formed from weathered...