Fingerprint forensics getting closer to the TV representation

Contrary to all the TV shows, in real life only 10% of fingerprints taken from crime scenes yield identifications usable in court. But now a new way of detecting and visualising fingerprints from crime scenes using colour-changing fluorescent films could lead to higher confidence identifications from latent (hidden) fingerprints on knives, guns, bullet casings and other metal surfaces.

The technique is the result of a collaboration between the University of Leicester, the Institut Laue-Langevin and the STFC’s ISIS pulsed neutron and muon source and was presented at the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Faraday Discussion in Durham.

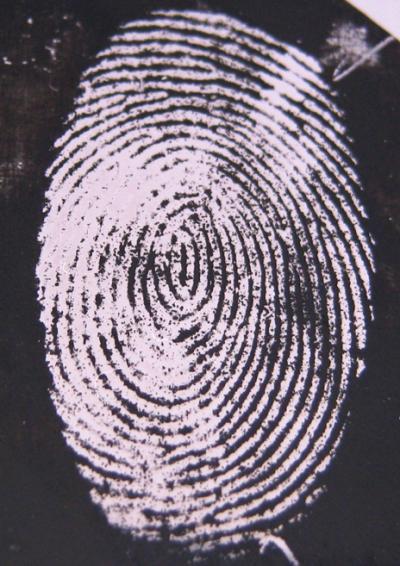

When your finger touches a surface, it leaves behind deposits of sweat and natural oils in a pattern that mirrors the ridges and troughs found on your fingertips. The odds of two individuals having identical fingerprints are 64 billion to 1, making them an ideal tool for identification in criminal investigations.

The greatest source of fingerprint forensic evidence comes from latent fingerprints - those not immediately visible to the eye, because they are less likely to be ‘wiped’. However, visualising these prints with sufficient clarity for positive identification often proves difficult. Despite the availability of several enhancement techniques, only 10% of fingerprints taken from crime scenes are of sufficient quality to be used in court.

Fingerprint patterns fall into three basic categories. First-level details include loops, whorls and arches. While these can clearly eliminate certain individuals, positive identification relies on the minutiae (or second-level detail) within the pattern: these include features such as ridge endings, crossovers (bridges), short independent ridges, islands, bifurcations, spurs, dots and lakes. There are also finer features (third-level detail) present in a fingerprint image: these include the detailed shapes of the ridges and individual sweat pores. While not currently used in fingerprint identification, there is considerable research interest in third-level detail, since it may in future permit analysis of smaller fragments of marks left by a finger, ie, partial fingerprints.

The classical approach to enhance latent print visibility is to apply a coloured powder that adheres to the sticky residue and provides a visual contrast to the underlying surface. However, these techniques require significant preservation of fingerprint material and are therefore vulnerable to ageing, environmental exposure or attempted washing of the fingerprint residue.

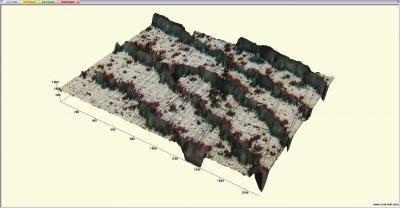

To address this, researchers from the University of Leicester have been working on a new technique that visualises fingerprints by exploiting their electrically insulating characteristics. Here, the fingerprint material acts like a mask or stencil, blocking an electric current that is used to deposit a coloured electroactive film. This directs the coloured film to the regions of bare surface between the fingerprint deposits, thereby creating a negative image of the print. Unlike conventional fingerprint visualisation reagents, the polymers used by the University of Leicester researchers are electrochromic, that is to say they change from one colour to another when subjected to an electrical voltage.

The technique is highly sensitive as even tiny amounts of insulating residue, just a few nanometres thick, can prevent polymer deposition on the metal below. As a result, much less fingerprint residue is required than is typical for other techniques. Also, because it focuses on the gaps between the fingerprint deposits, it can be used in combination with existing approaches such as powdering.

The team, led by Professor Robert Hillman, has developed this technique further by incorporating within the film fluorophore molecules that re-emit light of a third colour when exposed to light or any other form of electromagnetic radiation such as ultraviolet rays. Their success in combining the electrochromic and fluorescence approaches provides a significantly wider palette to ‘colour’ their films and two sets of ‘levers’ in the form of electricity and light to control and tune this colouration in order to achieve the best possible contrast with the underlying metal surface.

The addition of these large fluorescent tagging molecules required a conducting film that could undergo post-deposition chemical changes. Neutron reflectivity measurements were used to follow and quantify the deposition and functionalisation of the film with the fluorophores.

The exact position and distribution of the fluorophores within the film is key. Professor Hillman and colleagues needed the molecules to penetrate the deposited polymer layer without reaching the underlying metal surface, where their fluorescence is diminished. Using isotopic methods, the team were able to use neutrons at ILL and ISIS to label the different parts of the system and observe the behaviour of each to find the ideal conditions (temperature, polymer concentrations and reaction time) for the introduction of the fluorophores.

Using the new technique on laboratory-sourced fingerprints, Professor Hillman and colleagues have already demonstrated an improved ability to make positive identifications due to better sample resolution. However, the team are keen to stress these prints were taken under laboratory conditions. The next step is to apply it to fingerprints that have been exposed to more realistic scenarios, such as water, heat from a fire or cleaning agents.

Professor Robert Hillman said: “By using the insulating properties of the fingerprints to define their unique patterns and improving the visual resolution through these colour-controllable films, we can dramatically improve the accuracy of crime scene fingerprint forensics. From the images we have produced so far, we are achieving identification with high confidence using commonly accepted standards. This combination of optical absorption analysis with observation based on fluorescence is also opening up fingerprint analysis to a far wider set of samples, particularly those eroded by ageing or aggressive environments. The use of neutrons alongside spectroscopic techniques has been fundamental to understanding how this technique might work in practice and is evidence for what has been a truly collaborative partnership between these three institutions.”

Assistant Chief Constable Roger Bannister of Leicestershire Police said: “Fingerprints have been around in policing for over 100 years but this technique opens up new avenues for the detection of crime in the modern era. This technique potentially offers opportunities for quick results for the more serious crimes in a way that may still permit other forensic analysis to be performed to maximise the opportunities to recover forensic evidence. This follows Leicester University’s long tradition in the field of forensic discovery.”

Revealed: the complex composition of Sydney's beach blobs

Scientists have made significant progress in understanding the composition of the mysterious...

Sensitive gas measurement with a new spectroscopy technique

'Free-form dual-comb spectroscopy' offers a faster, more flexible and more sensitive way...

The chemistry of Sydney's 'tar balls' explained

The arrival of hundreds of tar balls — dark, spherical, sticky blobs formed from weathered...