Massless exotic particle found

The elusive Weyl fermion, a massless particle theorised 85 years ago, has been observed by two separate teams of researchers.

In 1928, Paul Dirac discovered a crucial equation in particle physics and quantum mechanics, now known as the Dirac equation. Very fast electrons were solutions to the Dirac equation. Moreover, the equation predicted the existence of anti-electrons, or positrons: particles with the same mass as electrons but having opposite charge. True to Dirac’s prediction, positrons were discovered in 1932 by the American physicist Carl Anderson.

In 1929, the German-born mathematician Hermann Weyl found another solution to the Dirac equation, this time massless. ‘Weyl fermions’, speculated to be one of the building blocks of subatomic particles, were conjectured to have no mass and to behave as both matter and antimatter — which has the same mass but opposite charge and other properties to regular matter — inside a crystal.

A year later, Wolfgang Pauli postulated the existence of the neutrino, which was then thought to be massless, and it was assumed to be the sought-after solution to the Dirac equation found by Weyl.

Neutrinos had not been detected yet in nature, but the case seemed to be closed. It would be decades before American physicists Frederick Reines and Clyde Cowan finally discovered neutrinos in 1957, and numerous experiments shortly thereafter indicated that neutrinos could have mass. In 1998, the Super-Kamiokande Collaboration neutrino observatory in Japan announced what had now been speculated for years: neutrinos have non-zero mass. This discovery opened a new question: what then was the zero-mass solution found by Weyl?

The observation of actual Weyl fermions was made by scientists at Princeton University in New Jersey and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and could herald a whole new age of better electronics. The research by both teams was published in the journal Science.

The researchers found the fermions independently by firing photons at crystals of the semi-metal tantalum arsenide, which has properties between an insulator and a conductor. The researchers noted that the Weyl fermions are not freestanding particles. Instead, they are quasiparticles (a ‘disturbance’ in a medium that behaves like a particle) that can only exist within the semi-metal crystals. In other words, they are electronic activity that behaves as if they were particles in free space. By shining beams of ultraviolet light and X-rays at these crystals, the researchers detected the telltale effects of Weyl fermions on those beams.

Particles are essentially divided into two groups. Fermions are said to be those that make up matter, while bosons are the force particles that hold them together. All other fermions are known to have mass, making the Weyl fermion unique among its ‘peers’.

Electrons, protons and neutrons all belong to the fermion class of particles. Unlike the other major class of particles, the bosons, which include photons, fermions can collide with each other — no two fermions can share the same state at the same position at the same time.

Surprisingly enough though, the Weyl fermions are very stable. They will also only interact with other Weyl fermions, staying on the same course and at the same speed until they do. This means that, unlike electrons, they can carry a charge for long distances without getting scattered or creating heat.

These unique properties could make the Weyl fermion incredibly useful for electronics in the future, including the development of quantum computing. For one thing, they can move independently of one another, and they can also create massless electrons. The consequence is they could flow more easily and lose less heat, making electrons more efficient.

Their basic nature means that Weyl fermions could provide a much more stable and efficient transport of particles than electrons, which are the principle particle behind modern electronics. Unlike electrons, the massless Weyl fermions possess a high degree of mobility; the particle’s spin is both in the same direction as its motion — which is known as being right-handed — and in the opposite direction in which it moves, or left-handed.

Another potentially useful quality of Weyl fermions is that they cannot move backwards — instead of bouncing away from obstacles, they zip through or around roadblocks. In contrast, electrons can scatter backwards when they collide with obstructions, hindering the efficiency of their flow and generating heat.

“Weyl fermions could be used to solve the traffic jams that you get with electrons in electronics — they can move in a much more efficient, ordered way than electrons,” said Zahid Hasan, a Princeton professor of physics who led one of the research teams.

The way that Weyl fermions are constrained from moving backwards is similar to how electrons behave in exotic materials called topological insulators. Such constraints can help current flow highly efficiently; Hasan says that electricity in these crystals can (theoretically) move at least twice as fast as it does in graphene and 1000 times faster than in conventional semiconductors, “and the crystals can be improved to do even better”. The upshot could be faster electronics that consume less energy. Power consumption and associated heating is currently limiting a further increase in processor speed in our computers.

In addition, Weyl fermions could also lead to new kinds of quantum computers that are more resistant to disruption. Quantum computers rely on states known as superpositions, in which a bit can essentially represent both one and zero at the same time. Superpositions offer the chance to solve previously intractable problems, but they are notoriously prone to collapsing if they interact with the environment.

How the Princeton team did it

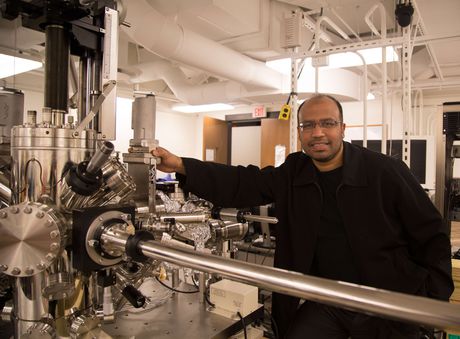

Prior to the Science paper, Hasan and his co-authors published a report in the journal Nature Communications in June that theorised that Weyl fermions could exist in a tantalum arsenide crystal. Guided by that paper, the researchers used the Princeton Institute for the Science and Technology of Materials (PRISM) and Laboratory for Topological Quantum Matter and Spectroscopy in Princeton’s Jadwin Hall to research and simulate dozens of crystal structures before seizing on the asymmetrical tantalum arsenide crystal, which has a differently shaped top and bottom.

The crystals were then loaded into a two-storey device known as a scanning tunnelling spectromicroscope that is cooled to near absolute zero and suspended from the ceiling to prevent even atom-sized vibrations. The spectromicroscope determined if the crystal matched the theoretical specifications for hosting a Weyl fermion. “It told us if the crystal was the house of the particle,” Hasan said.

The Princeton team took the crystals passing the spectromicroscope test to the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California to be tested with high-energy accelerator-based photon beams. Once fired through the crystal, the beams’ shape, size and direction indicated the presence of the long-elusive Weyl fermion.

First author Su-Yang Xu, a postdoctoral research associate in Princeton’s Department of Physics, said that the work was unique for encompassing theory and experimentalism.

“The nature of this research and how it emerged is really different and more exciting than most of other work we have done before,” Xu said. “Usually, theorists tell us that some compound might show some new or interesting properties, then we as experimentalists grow that sample and perform experiments to test the prediction. In this case, we came up with the theoretical prediction ourselves and then performed the experiments. This makes the final success even more exciting and satisfying than before.”

Revealed: the complex composition of Sydney's beach blobs

Scientists have made significant progress in understanding the composition of the mysterious...

Sensitive gas measurement with a new spectroscopy technique

'Free-form dual-comb spectroscopy' offers a faster, more flexible and more sensitive way...

The chemistry of Sydney's 'tar balls' explained

The arrival of hundreds of tar balls — dark, spherical, sticky blobs formed from weathered...