Plasma-modified graphene enhances gas sensors

Japanese researchers have found a way to improve gas-sensing technology by treating graphene sheets with plasma under different conditions, resulting in superior sensing performance compared to pristine graphene.

Gas-sensing technologies play a vital role in our modern world — from ensuring our safety in homes and workplaces to monitoring environmental pollution and industrial processes — but they often face limitations in their sensitivity, response time and power consumption. To account for these drawbacks, recent developments in gas sensors have focused on carbon nanomaterials, including graphene — a versatile and relatively inexpensive material that can provide exceptional sensitivity at room temperature while consuming minimal power.

Against this backdrop, a research team led by Associate Professor Tomonori Ohba from Chiba University explored a promising avenue to improve graphene’s sensing properties even further. The team investigated how and why graphene sheets treated by plasma with different gases can lead to enhanced sensitivity for ammonia (NH3) — a toxic compound — with their results published in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

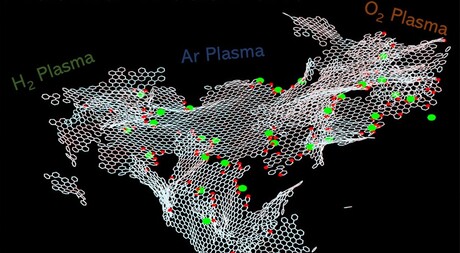

The researchers produced graphene sheets and applied a plasma treatment to them under argon (Ar), hydrogen (H2) or oxygen (O2) environments. This treatment ‘functionalised’ graphene, meaning that it modified the surface of the graphene sheets by attaching specific chemical groups and creating controlled defects, serving as additional binding sites for gas molecules like NH3.

After treatment, the researchers employed a variety of advanced spectroscopic techniques and theoretical calculations to shed light on the precise chemical and structural changes the graphene sheets underwent. They found that the gas used during plasma treatment led to the creation of different types of defects on the graphene sheets.

“The O2 plasma treatment induced oxidation of the graphene, producing graphoxide, whereas the H2 plasma treatment induced hydrogenation, producing graphane,” Ohba said.

“Spectroscopic analysis suggested that graphoxide had carbon vacancy-type defects, graphane had sp3-type defects, and Ar-treated graphene had both types of defects,” she continued. An sp3-type defect is a structural change where a carbon atom in graphene shifts from having three bonds in a flat plane to forming four bonds in a tetrahedral arrangement, often due to hydrogen atoms attaching to the surface.

Interestingly, introducing these defects into the graphene sheets greatly enhanced their performance for sensing NH3. Since NH3 binds more easily to defects rather than to pristine graphene, the electrical conductivity of functionalised sheets changed more noticeably when exposed to NH3. This property can be leveraged in gas-sensing devices to detect and quantify the presence of NH3. Graphoxide, in particular, exhibited the greatest changes in sheet resistance (the inverse of conductivity) when exposed to NH3 — these changes were as high as 30%.

The team also tested whether functionalised graphene sheets could withstand repeated exposure to NH3 without degrading their gas-sensing performance. Although some irreversible changes in sheet resistance were observed, some significant changes were fully reversible and cyclable.

“The results showed that functionalising graphene structures with plasma generated noble materials with a superior NH3 gas-sensing performance compared with pristine graphene,” Ohba said. The research could therefore pave the way for next-generation, wearable gas-sensing devices for everyday use.

“As graphene is among the thinnest possible sheets with gas permeability, the functionalised graphene sheets developed in this work could be used in daily wearable devices,” Ohba said. “Thus, in the future, anyone would be able to detect harmful gases in their surroundings.”

Benchtop NMR used to assess heart disease risk

The breakthrough will enable more accessible, high-throughput cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk...

Activated gold helps visualise drug movement in the body

Gold nanoparticles are promising drug carriers for cancer therapy and targeted drug delivery, but...

Laser-powered device could detect microbial fossils on Mars

The first life on Earth formed four billion years ago, as microbes living in pools and seas: but...