Spectral patterns of benzene dimer finally deciphered

Although the double benzene molecule tried to reveal its structure in experiments in 1993, chemists at the time were unable to find an explanation for the spectral peaks they saw. Now, 20 years later, Radboud University Nijmegen theoretical chemist Prof Ad van der Avoird has come up with a theory that exactly describes the position of two benzene rings in relation to one another and their possible motion. Together with colleague Prof Gerard Meijer and an experimental group in Berlin, he published the model in a Very Important Paper in Angewandte Chemie International Edition on 15 April.

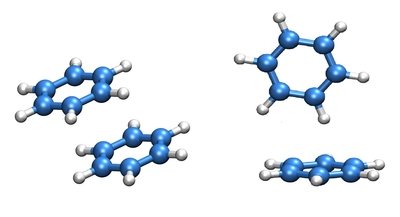

Benzene is a molecule that has a structure in the shape of a hexagonal ring. Two benzene rings can form a stable bimolecule (a dimer). There are two different ways in which they can be positioned relative to one another: one flat on top of the other or one lying flat and the other upright on top. If the rings are part of a larger molecule their configuration influences the folding of the molecule or the binding between two such molecules, which in turn greatly affects the molecule’s biological activity.

From experiment to theory

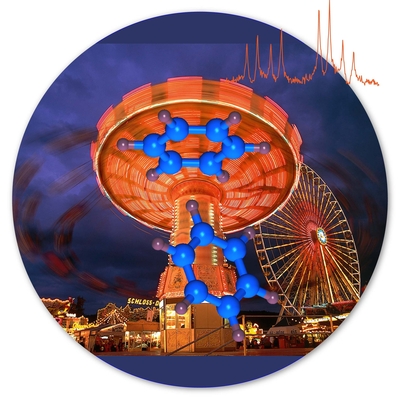

A spectrum of the benzene dimer was first recorded in 1993, with the aim to find out more about its structure and dynamics. The experiments produced characteristic patterns with four peaks, which no one could decipher for 20 years. Scientists from Berlin, Hannover and Hamburg recently repeated the experiments using the most advanced equipment in the hope that this, together with calculations made by van der Avoird, would clarify the issue. However, the problem remained unsolved. Now, using a new theoretical model and the experimental data gathered in Berlin, the spectral patterns have been successfully deciphered and the dynamics that cause them explained.

Van der Avoird explained: “The old model was not wrong, but it was very complicated. As a result, the computer calculations made using the model were too inaccurate to be able to calculate the peak patterns. I therefore needed to pare the model down to the basics, after which the spectral patterns just rolled out of the calculations. The key to success was the insight that the rings rotate in synchronisation. They work together to switch rapidly between one energy minimum and another. This results, via the quantum tunnelling process, in the recorded peak patterns.”

The van der Waals forces described in the model are certainly one of the cornerstones of chemistry, says van der Avoird, though he dare not say whether his observations will make it into the chemistry textbooks. Even so, there are certainly practical applications. “For example, large-scale simulations are often used to develop new drugs in the pharmaceutical industry and these require an understanding of the van der Waals forces between the receptor and the potential drug molecules.”

Van der Avoird will publish the article together with the experimental researchers from Berlin, Hannover and Hamburg. Co-author Gerard Meijer, currently President of the Executive Board at Radboud University Nijmegen, was director of the Department of Molecular Physics at the Fritz Haber Institute in Berlin at the time the research was conducted there. The article was accepted very quickly (within two weeks) and marked VIP - Very Important Paper - an accolade only achieved by the top 5% of the articles published.

'Phantom chemical' in drinking water finally identified

Researchers have discovered a previously unknown compound in chloraminated drinking water —...

Flinders facility to use the micro realm to understand the past

AusMAP aims to revolutionise the ways scientists address key questions and grand challenges in...

A new, simpler method for detecting PFAS in water

Researchers demonstrated that their small, inexpensive device is feasible for identifying various...