'Placenta-on-a-chip' models caffeine transport from mother to foetus

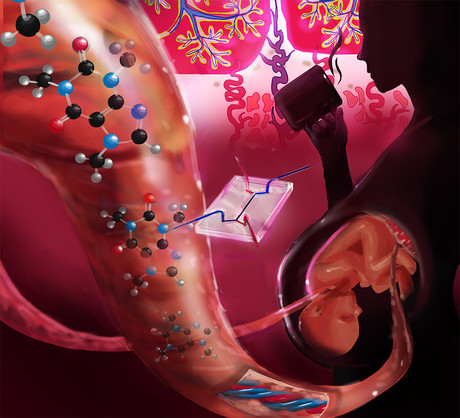

US engineers have used microfluidic technology to create a ‘placenta-on-a-chip’ that models how compounds can be passed from a mother to a foetus, in a breakthrough that will give scientists a better understanding of an important but temporary organ.

Developing inside a woman’s uterus during pregnancy, the placenta (through the umbilical cord) provides oxygen and nutrients to the foetus and removes waste from the foetal bloodstream. But animal models of the placenta don’t translate well to human health, and because of its temporary nature there haven’t been a lot of human studies — and those that have been done have shown inconsistent results.

“We looked at different organs and decided on developing a placenta model because there aren’t many studies on this important temporary organ,” said Nicole Hashemi, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Iowa State University and leader of the project — one that would require four years of challenging work.

First, the engineers had to design the microfluidics — they ultimately decided on a model featuring two microchannels just 100 millionths of a metre high and 400 millionths of a metre wide. Then they had to figure out how to effectively grow cells on either side of a porous, biocompatible membrane that would separate the two channels and represent the placental barrier. They also had to identify the right compound to test using the model so they could understand transport from the maternal side to the foetal side.

The engineers decided on caffeine for their initial study, given that health authorities recommend restricting caffeine intake during pregnancy due to potential effects on the foetus. It’s also an important question to Hashemi, who admitted, “I drink a lot of tea.”

The researchers introduced a caffeine concentration of 0.25 mg/mL — a concentration deemed safe by US Food and Drug Administration guidelines — to the maternal side of the placenta model for an hour and then monitored changes over 7.5 hours. At six and a half hours, the maternal side reached a steady caffeine concentration of 0.1513 mg/mL. The foetal side reached a steady concentration of 0.0033 after five hours.

The results of the study, published in the journal Global Challenges, thus suggest that caffeine from mother’s tea or coffee does make it into the baby’s bloodstream.

Now that the model has been demonstrated, Hashemi said it is being used by research partners at The Ohio State University College of Medicine to study how different drugs move through the placental barrier. There has also been interest in studying how environmental toxins are transported from mother to foetus, she said.

Future studies could include personalising the technology — actually tuning the model with cells from a mother or foetus to help prescribe medicines or dosages. And maybe one day researchers could study the effects of placental transport of chemicals and compounds on individual cells.

“We are trying to model the real placenta,” Hashemi said. “Now that we have this placenta-on-a-chip technology in place, we can collaborate with researchers working on all kinds of projects.”

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

Chewing gum can shed microplastics into saliva, study finds

Most of the microplastics detached from gum within the first two minutes of chewing, with the act...

Widespread applications of shake flask off-gas analysis across biotechnology

Despite the emergence of more sophisticated bioreactor systems, shake flasks continue to play a...

Scientists may finally know what makes Mars red

The water-rich iron mineral ferrihydrite may be the main culprit behind Mars's reddish dust,...