Limpet-inspired biomaterial features super strength

An interdisciplinary research team from the University of Portsmouth has grown an extremely strong biomaterial inspired by limpets, with their results published in the journal Nature Communications.

Limpets are aquatic, snail-like molluscs that use a tongue bristling with tiny microscopic teeth to scrape food off rocks and into their mouths. These teeth contain a hard yet flexible composite, which in 2015 was found to be the strongest known biologically occurring material — far stronger than spider silk and comparable to man-made substances including carbon fibre and Kevlar.

The research team has now successfully mimicked limpet tooth formation in a laboratory and used it to create a new composite biomaterial — one which has the potential to be upscaled into something that could rival the strength and flexibility of synthetics, but be disposed of without generating harmful waste products.

“Fully synthetic composites like Kevlar are widely used, but the manufacturing processes can be toxic, [and] the materials difficult and expensive to recycle,” said lead author Dr Robin Rumney.

“Here we have a material which potentially is much more sustainable in terms of how it’s sourced and made, and at the end of its life can be biodegraded.”

It’s thought the secret to the limpet tooth’s strength is a unique structure containing a combination of flexible tightly packed fibres of a scaffold material called chitin, interspersed with fine crystals of an iron-containing mineral called goethite. Those fibres are laced through each other in much the same way as carbon fibres can be used to strengthen plastic.

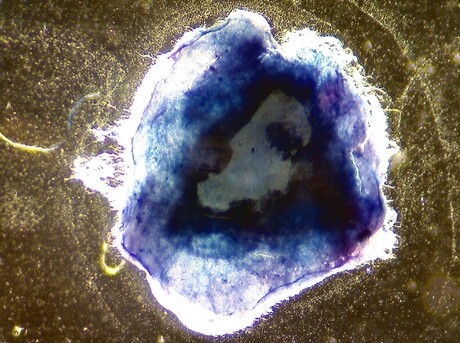

The researchers developed methods which allowed these cell populations to grow outside of their natural environment on serum-coated glass, where they deposited chitin and iron oxide just as in the limpet tooth. Remarkably, after two weeks they self-organised into structures that resembled the limpet organ, known as the radula, which makes the teeth. Rumney even found ways of growing ribbons of teeth from tissue samples and individual teeth from populations containing stem cells — a process which took him six months to perfect.

After successfully replicating the limpet tooth formation, the team was then able to produce samples of biomaterial half a centimetre wide. They did this by mineralising a sheet of chitin, which is a waste by-product of the fishing industry found in the exoskeletons of crustaceans, crabs and shrimps.

Now that proof of concept has been established, Rumney wants to explore the possibility that these minidiscs can be scaled up and mass manufactured. He said, “Our next step is to find other ways of getting the iron formation occurring, so we’re studying the secretions of the limpet cells to better understand that. If it works really well, then we already have the gene readouts of the organ so we can lift the genes of interest out, and hopefully put them into bacteria or yeast to grow them at scale.

“Obviously we have a plastics crisis in the oceans right now, and I think it’s a nice symmetry that we can learn from a sea creature how to better protect them by replacing the use of plastics with a biological substitute.”

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

'Optical tweezers' could help study living cells

Physicists are using the tweezers to measure activity within microscopic systems over timeframes...

Aerosol test for airborne bird flu developed

The low-cost sensor detects the virus at levels below an infectious dose and could lead to rapid...

Superelastic alloy functions in extreme temperatures

The titanium-aluminium superelastic alloy is not only lightweight but also strong, offering the...