Loofah-inspired hydrogel for water purification

Access to clean water is being strained as the human population increases and contamination impacts freshwater sources — and while there are devices in development that can clean dirty water using sunlight, these can only produce a dozen or so litres of water each day. Now researchers from Princeton University have devised a sunlight-powered porous hydrogel, inspired by loofah sponges, that could potentially purify enough water to satisfy someone’s daily needs.

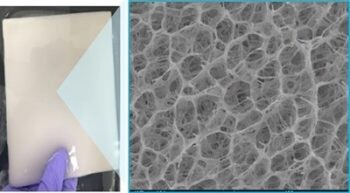

Previously, researchers have suggested that sunlight-driven evaporation could be a low-energy way to purify water, but this approach doesn’t work well when it’s cloudy. One solution could be temperature-responsive hydrogels, specifically poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide) (PNIPAm), that switch from absorbing water at cooler temperatures to repelling it when heated. However, conventional PNIPAm gels can’t generate clean water fast enough to meet people’s daily needs because of their closed-off pores. Conversely, natural loofahs, which many people use to exfoliate in the shower, have large, open and interconnected pores.

Rodney Priestley, Xiaohui Xu and colleagues wanted to replicate the loofah’s structure in a PNIPAm-based hydrogel, yielding a material that could rapidly absorb water at room temperature and rapidly release purified water when heated by the sun’s rays under bright or cloudy conditions. Their work was published in the journal ACS Central Science.

The researchers used a water and ethylene glycol mixture as a uniquely different polymerisation medium to make a PNIPAm hydrogel with an open pore structure, similar to a natural loofah. Then they coated the opaque hydrogel’s inner pores with polydopamine (PDA) and poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) (PSMBA), and tested this material using an artificial light equivalent to the power of the sun. It absorbed water at room temperature and, when heated by the artificial light, released 70% of its stored water in 10 minutes — a rate four times greater than the one for a previously reported absorber gel — offering the potential to meet a person’s daily demand. Even under lower light conditions, replicating partly cloudy skies, it took 15 to 20 minutes for the material to release a similar amount of stored water.

Finally, the loofah-like material was tested on samples polluted with organic dyes, heavy metals, oil and microplastics. In all of the tests, the gel made the water substantially cleaner. For example, in two cycles of treatment, water samples with around 40 parts per million (ppm) chromium were absorbed, then released with less than 0.07 ppm chromium — the allowable limit for drinking water. The researchers say their hydrogel structure could also be useful in additional applications, such as drug delivery, smart sensors and chemical separations.

Microplastics found to alter the human gut microbiome

Microplastic-treated cultures showed a consistent and significant increase in acidity (lower pH...

Sustainable, self-repairing, antimicrobial polymers developed

From medicine to electronics and optics, new materials developed by scientists at Kaunas...

A better way to create conductive polymers

New research disproves the longstanding belief that to create conductive polymers, substances...