Proteomics and the formation of long-term memories

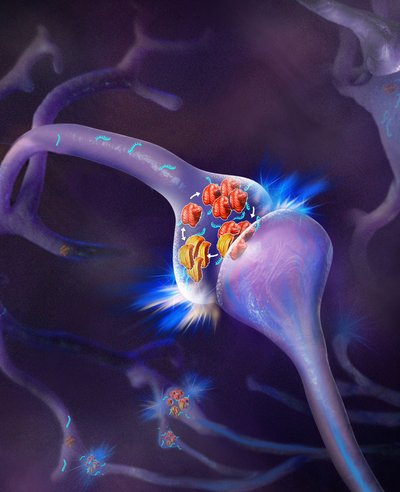

Memories are maintained by synapses, the connections between neurons, but how do these synapses stay strong and keep memories alive for decades? Neuroscientists at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research have discovered a major clue from a study in fruit flies: hardy, self-copying clusters or oligomers of a synapse protein are an essential ingredient for the formation of long-term memory.

The finding supports a surprising new theory about memory and may have a profound impact on explaining other oligomer-linked functions and diseases in the brain, including Alzheimer’s disease and prion diseases.

“Self-sustaining populations of oligomers located at synapses may be the key to the long-term synaptic changes that underlie memory; in fact, our finding hints that oligomers play a wider role in the brain than has been thought,” says Kausik Si, PhD, an associate investigator at the Stowers Institute, and senior author of the new study, which was published in the 27 January 2012 online issue of the journal Cell.

Si’s investigations in this area began nearly a decade ago during his doctoral research in the Columbia University laboratory of Nobel-winning neuroscientist Eric Kandel. He found that in the sea slug Aplysia californica, which has long been favoured by neuroscientists for memory experiments because of its large, easily-studied neurons, a synapse-maintenance protein known as CPEB (cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein) has an unexpected property.

A portion of the structure is self-complementary and - much like empty egg cartons - can easily stack up with other copies of itself. CPEB thus exists in neurons partly in the form of oligomers, which increase in number when neuronal synapses strengthen. These oligomers have a hardy resistance to ordinary solvents, and within neurons may be much more stable than single-copy monomers of CPEB. They also seem to actively sustain their population by serving as templates for the formation of new oligomers from free monomers in the vicinity.

CPEB-like proteins exist in all animals, and in brain cells they play a key role in maintaining the production of other synapse-strengthening proteins. Studies by Si and others in the past few years have hinted that CPEB’s tendency to oligomerise is not merely incidental, but is indeed essential to its ability to stabilise longer-term memory. “What we’ve lacked till now are experiments showing this conclusively,” Si says.

In the new study, Si and his colleagues examined a Drosophila fruit fly CPEB protein known as Orb2. Like its counterpart in Aplysia, it forms oligomers within neurons. “We found that these Orb2 oligomers become more numerous in neurons whose synapses are stimulated, and that this increase in oligomers happens near synapses,” says lead author Amitabha Majumdar, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in Si’s lab.

The key was to show that the disruption of Orb2 oligomerisation on its own impairs Orb2’s function in stabilising memory. Majumdar was able to do this by generating an Orb2 mutant that lacks the normal ability to oligomerise yet maintains a near-normal concentration in neurons. Fruit flies carrying this mutant form of Orb2 lost their ability to form long-term memories. “For the first 24 hours after a memory-forming stimulus, the memory was there, but by 48 hours it was gone, whereas in flies with normal Orb2 the memory persisted,” Majumdar says.

Si and his team are now following up with experiments to determine for how long Orb2 oligomers are needed to keep a memory alive. “We suspect that they need to be continuously present, because they are self-sustaining in a way that Orb2 monomers are not,” says Si.

The team’s research also suggests some intriguing possibilities for other areas of neuroscience. This study revealed that Orb2 proteins in the Drosophila nervous system come in a rare, highly oligomerisation-prone form (Orb2A) and a much more common, much less oligomerisation-prone form (Orb2B). “The rare form seems to be the one that is regulated, and it seems to act like a seed for the initial oligomerisation, which pulls in copies of the more abundant form,” Si says. “This may turn out to be a basic pattern for functional oligomers.”

The findings may help scientists understand disease-causing oligomers too. Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease, as well as prion diseases such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, all involve the spread in the brain of apparently toxic oligomers of various proteins. One such protein, strongly implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, is amyloid beta; like Orb2 it comes in two forms, the highly oligomerising amyloid-beta-42 and the relatively inert amyloid-beta-40. Si’s work hints at the possibility that oligomer-linked diseases are relatively common in the brain because the brain evolved to be relatively hospitable to CPEB proteins and other functional oligomers, and thus has fewer mechanisms for keeping rogue oligomers under control.

Other researchers who contributed to the work include Wanda Colón Cesario, Erica White-Grindely, Huoqin Jian, Fangzhen Ren, Mohammed ‘Repon’ Khan, Liying Li, Edward Man-Lik Choi, Kasthuri Kannan, Feng Li, Jay Unruh and Brian Slaughter at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research in Kansas City, Missouri.

The research was supported by the Searle Foundation, the March of Dimes Basil O’Connor Starter Award, the Klingenstein Foundation and the McKnight Foundation.

Stowers Institute for Medical Research

Blood test for chronic fatigue syndrome developed

The test addresses the need for a quick and reliable diagnostic for a complex,...

Droplet microfluidics for single-cell analysis

Discover how droplet microfluidics is revolutionising single-cell analysis and selection in...

PCR alternative offers diagnostic testing in a handheld device

Researchers have developed a diagnostic platform that uses similar techniques to PCR, but within...