Fetuses can fight infections within the womb

A research team led by Duke-NUS Medical School has discovered that fetuses are not as defenceless as once thought; they can actually fight infections from within the womb. This could significantly change the way doctors protect fetuses from infections that lead to serious health conditions, like microcephaly, where the baby’s head is significantly smaller than expected for its age.

It had previously been thought that the mother’s immune system was the sole source of protection from infection for a fetus, but the new study, published in the journal Cell, found that a fetus has a functional immune system that is well-equipped to combat infections in its developing nervous system. This could potentially benefit women who contract infections during pregnancy, putting the life of their fetus at risk.

“Early in pregnancy, a fetus cannot survive on its own and we have always assumed that it mostly relies on the mother’s immune system for protection against infections,” said Associate Professor Ashley St John, lead author on the study. “However, we found that the fetus’s own immune system is already able to mount defences against infections much earlier than previously thought.”

Investigating further, the scientists studied the fetal immune response in a preclinical model using Zika virus strains from around the world. They found that immune cells react differently to infection — either taking on a protective role and reducing damage to the fetus’s developing brain or harming the fetus’s brain by causing non-protective inflammation.

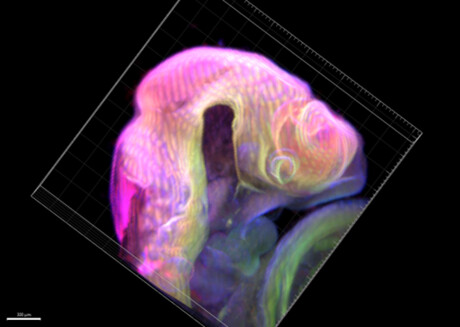

The study revealed new insights into the role of microglia, a type of immune cell found in the brain. Using human brain models known as organoids or mini-brains, the researchers confirmed that these cells take on a protective role during an infection and are crucial to the fetal immune system’s defence against pathogens.

Monocytes — white blood cells produced in the bone marrow — were another type of immune cell that the researchers studied. The team found that besides being drawn to the fetal brain during an infection, they triggered detrimental inflammation in the brain, killing brain cells instead of eliminating the virus. While it had previously been shown that monocytes’ harmful nature only manifests after birth, it turns out that these immune cells can also cause damage to a developing fetal brain before birth.

Additionally, monocytes produce highly reactive molecules known as reactive oxygen species that help the body combat pathogens by alerting cells to a pathogen, a state in which they release inflammatory signals. However, the researchers observed that an increased release of a particular inflammatory signal, called nitric oxide synthase-2 (NOS2), caused neuron damage when combined with reactive oxygen species in large volumes. Just as bleach can damage the fibres of a piece of clothing when used in excess, so too can immune responses harm a fetus’s brain if they are not properly regulated.

In response to this finding, the scientists used an experimental anti-inflammatory drug to block the function of NOS2. This led to the reduction of non-protective inflammation induced by monocytes in the brain and protected the foetal brain from the damage that Zika infections can cause.

St John said the study brings a fresh perspective to the fight against congenital disorders, particularly those caused by diseases transmitted from mothers to fetuses during pregnancy.

“Our work has shown that the immune responses of fetuses can be either protective or harmful,” she said. “Knowing how various immune cells contribute to fetal immune protection will be important in our continued search for ways to improve pregnancy outcomes.

“We hope that with further testing, we can establish the safety of the anti-inflammatory drug so that it can be developed into a viable form of treatment that protects foetuses from harmful inflammation in their brains.”

Mini lung organoids could help test new treatments

Scientists have developed a simple method for automated the manufacturing of lung organoids...

Clogged 'drains' in the brain an early sign of Alzheimer’s

'Drains' in the brain, responsible for clearing toxic waste in the organ, tend to get...

World's oldest known RNA extracted from woolly mammoth

The RNA sequences are understood to be the oldest ever recovered, coming from mammoth tissue...