Garvan researchers find a new form of DNA

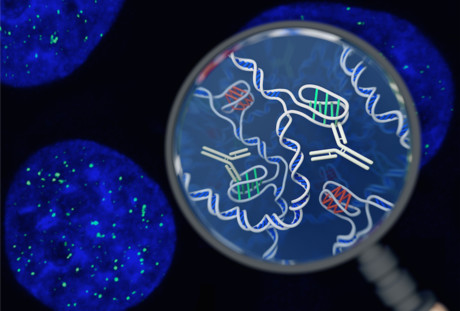

In a world first, researchers from the Garvan Institute of Medical Research have identified a new four-stranded ‘tangled knot’ structure inside living cells.

The new structure — called the i-motif — has never before been directly seen inside living cells. The findings have been published in the journal Nature Chemistry.

Deep inside the cells in our body lies our DNA. The information in the DNA code — all six billion A, C, G and T letters — provides precise instructions for how our bodies are built, and how they work.

The iconic ‘double helix’ shape of DNA has captured the public imagination since 1953, when James Watson and Francis Crick famously uncovered the structure of DNA. However, it’s now known that short stretches of DNA can exist in other shapes, in the laboratory at least — and scientists suspect that these different shapes might play an important role in how and when the DNA code is ‘read’. The new shape looks entirely different to the double-stranded DNA double helix.

“When most of us think of DNA, we think of the double helix,” said Daniel Christ, Associate Professor and Head, Antibody Therapeutics Lab, Garvan, who co-led the research.

“This new research reminds us that totally different DNA structures exist — and could well be important for our cells.”

“In the knot structure, C letters on the same strand of DNA bind to each other — so this is very different from a double helix, where ‘letters’ on opposite strands recognise each other, and where Cs bind to Gs [guanines],” said Marcel Dinger, Associate Professor and Head, Kinghorn Centre for Clinical Genomics, Garvan, who co-led the research with Professor Christ.

Although researchers have seen the i-motif before and have studied it in detail, it has only been witnessed in vitro — that is, under artificial conditions in the laboratory, and not inside cells.

In fact, scientists in the field have debated whether i-motif ‘knots’ would exist at all inside living things, a question that is resolved by the new findings.

To detect the i-motifs inside cells, the researchers developed a precise new tool — a fragment of an antibody molecule — that could specifically recognise and attach to i-motifs with a very high affinity. Until now, the lack of an antibody that is specific for i-motifs has severely hampered the understanding of their role.

Crucially, the antibody fragment didn’t detect DNA in helical form, nor did it recognise ‘G-quadruplex structures’ (a structurally similar four-stranded DNA arrangement).

With the new tool, researchers uncovered the location of ‘i-motifs’ in a range of human cell lines. Using fluorescence techniques to pinpoint where the i-motifs were located, they identified numerous spots of green within the nucleus which indicate the position of i-motifs.

“What excited us most is that we could see the green spots — the i-motifs — appearing and disappearing over time, so we know that they are forming, dissolving and forming again,” said Dr Mahdi Zeraati, whose research underpins the study’s findings.

The researchers showed that i-motifs mostly form at a particular point in the cell’s ‘life cycle’ — the late G1 phase, when DNA is being actively ‘read’. They also showed that i-motifs appear in some promoter regions (areas of DNA that control whether genes are switched on or off) and in telomeres, ‘end sections’ of chromosomes that are important in the ageing process.

Dr Zeraati said, “We think the coming and going of the i-motifs is a clue to what they do. It seems likely that they are there to help switch genes on or off, and to affect whether a gene is actively read or not.”

“We also think the transient nature of the i-motifs explains why they have been so very difficult to track down in cells until now,” added Christ.

“It’s exciting to uncover a whole new form of DNA in cells — and these findings will set the stage for a whole new push to understand what this new DNA shape is really for, and whether it will impact on health and disease,” said Dinger.

Colossal announces 'de-extinction' of the dire wolf

Colossal Biosciences has announced what it describes as the rebirth of the dire wolf, which would...

Aspirin could prevent some cancers from spreading

The research could lead to the targeted use of aspirin to prevent the spread of susceptible types...

Heat-induced heart disease is killing Australians

Hot weather is responsible for an average of almost 50,000 years of healthy life lost to...