Genomic elements preserved across 700 million years of evolution

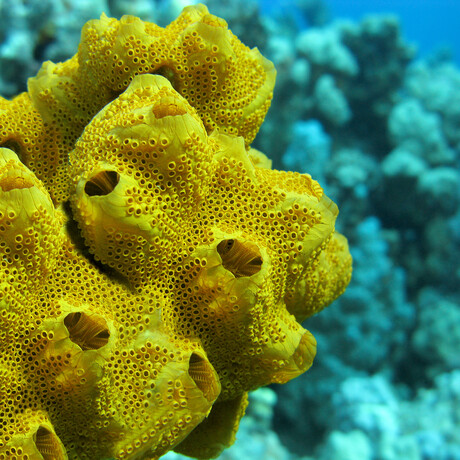

In a discovery 700 million years in the making, Australian scientists have found that humans — and most likely the entire animal kingdom — share important genetic mechanisms with a prehistoric sea sponge that comes from the Great Barrier Reef.

Published in the journal Science, the team’s research reveals that some elements of the human genome are functioning the same way as in the jelly-like sea sponge, which dominated life on planet Earth even before the dinosaurs. The mechanism drives gene expression — a key to species diversity across the animal kingdom — and has incredibly been preserved across 700 million years of evolution.

“This is a fundamental discovery in evolution and the understanding of genetic diseases, which we never imagined was possible,” said lead researcher Dr Emily Wong, from the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute and UNSW Sydney. “It was such a far-fetched idea to begin with, but we had nothing to lose so we went for it.

“We collected sea sponge samples from the Great Barrier Reef, near Heron Island. At The University of Queensland, we extracted DNA samples from the sea sponge and injected it into a single cell from a zebrafish embryo. Without harming the zebrafish, we then repeated the process at the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute with hundreds of embryos, inserting small DNA samples from humans and mice as well.

“What we found is, despite a lack of similarity between the sponge and humans due to millions of years of evolution, we identified a similar set of genomic instructions that controls gene expression in both organisms. We were blown away by the results!”

According to Dr Wong and her colleagues, the sections of DNA that are responsible for controlling gene expression — known as ‘enhancers’ — are notoriously difficult to find, study and understand. Even though they make up a significant part of the human genome, researchers are only at the beginnings of understanding this genetic ‘dark matter’.

“They can’t generally be found by comparing sequences like we can with genes, because they evolve so rapidly,” Dr Wong explained.

“Trying to find these regions based on the genome sequence alone is like looking for a light switch in a pitch-black room. And that’s why, up to this point, there has not been a single example of a DNA sequence enhancer that has been found to be conserved across the animal kingdom.

“So just the fact that we’re able to identify these sequences, despite such a long period of evolutionary time, is very exciting.”

Working alongside Dr Wong was her husband and co-senior author on the paper, Associate Professor Mathias Francois from the Centenary Institute. He said, “This work is incredibly exciting as it allows us to better ‘read’ and understand the human genome, which is an incredibly complex and ever-changing instruction manual of life.

“The team focused on an ancient gene that is important in our nervous system but which also gave rise to a gene critical in heart development.” The findings, he said, will drive biomedical research and future healthcare benefits too.

“Being able to better interpret the human genome aids our understanding of human processes, including disease and disorders, many of which have a genetic basis. The more we know about how our genes are wired, the better we are able to develop new treatments for diseases.”

Professor Marcel Dinger, Head of UNSW’s School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences (BABS), said there is much about the information stored in the genome that we still don’t understand fully. “This study is an important step towards decoding life’s programming language — the new knowledge it presents will help inform future research across the medical, technology and life sciences fields,” he said.

“It’s terrific to see such important research recognised by one of the world’s most prestigious scientific journals.”

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

Aspirin could prevent some cancers from spreading

The research could lead to the targeted use of aspirin to prevent the spread of susceptible types...

Heat-induced heart disease is killing Australians

Hot weather is responsible for an average of almost 50,000 years of healthy life lost to...

Call for greater diversity in genomics research

A gene variant common in Oceanian communities has been misclassified as a potential cause of...