Healthy kidneys could be key to surviving malaria

A research team led by Portugal’s Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (IGC) have found that the kidneys could well be the line separating life from death in malaria, taking the lead in iron recycling and stopping the body from surrendering to the invading parasite. Their study has been published in the journal Cell Reports.

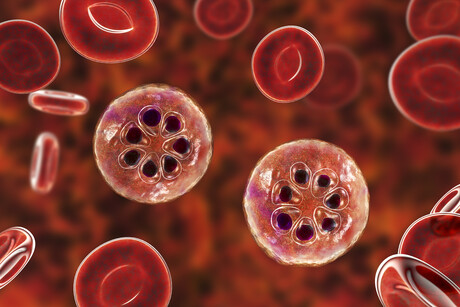

Severe and often lethal outcomes of malaria, such as acute kidney injury, emerge as the Plasmodium parasite invades the host’s red blood cells. As the parasite multiplies, it destroys these cells and causes anaemia, weakening the host’s health. In normal conditions, immune cells called macrophages recycle the iron released from damaged or old red blood cells to form new ones. But the capacity of this system is quickly exhausted when there is mass destruction, as in malaria; as a result, the patient develops severe anaemia and has a higher risk of dying. The IGC research found that when acute kidney injury and anaemia occur simultaneously, they act synergistically to substantially increase the risk of death.

“It is easy to understand, through its colour, that the mice we study get rid of the by-products of red blood cells’ destruction through urine,” said Susana Ramos, who co-led the recent study. “We began to realise that these animals also had lots of iron in their urine, but they could not possibly be getting rid of it all, even more so because these sick mice do not eat enough to sustain the needed levels of this essential micronutrient. So we thought there must be a population of kidney cells that reabsorbs and recycles iron, to maintain some degree of normality in these anaemic mice.”

In a previous study, these cells, known as renal proximal tubule cells, had already proven their importance in getting rid of toxic by-products that promote severe forms of malaria. Here, this cell population demonstrated their role in preventing death from severe forms of malaria. Qian Wu, the first author of the study, found that these kidney cells alter their genetic program so that they can absorb and store iron. Later, they put the iron back in circulation, allowing for new red blood cells to form.

“We were not expecting kidneys to have such an immediate role in re-establishing the development of these blood cells,” Wu revealed.

By becoming the main organ responsible for storing and redistributing iron during malaria, the kidneys determine the outcome of this disease. To understand the implications of this mechanism, the researchers created mice without ferroportin, the gene that allows kidney cells to export iron. The results were surprising: the animals developed severe anaemia and died, a clear example of how a simple cellular mechanism can have profound effects on the whole body. By re-establishing the circuit of iron and the number of red blood cells, the kidneys put a brake on anaemia, ensuring that the different organs receive oxygen and continue to function when the host is infected.

“This finding is a clear demonstration of how the metabolism of an infected host can be re-wired to determine the outcome of an infection — in this case, malaria,” said Miguel Soares, the principal investigator on the study.

These findings could be important for providing a personalised prognosis to infected patients, with Soares noting, “People with some genetic mutations in this cellular iron exporter are less prone to develop severe anaemia.” On the other hand, if the kidney cells cannot export the iron they absorb, the patients might become more susceptible to developing acute kidney injury and anaemia. The researchers are now thinking about therapeutic strategies directed to this metabolic pathway.

Five scenarios for the future of Antarctic life

A team of Australian and international researchers have predicted five possible outcomes for how...

Could this biosensor bypass labs with onsite PFAS detection?

La Trobe University has developed a portable biosensor that may allow rapid, onsite detection of...

How a tiny worm changed a decade of scientific thinking

A tiny roundworm has helped University of Queensland scientists rethink the way sensory nerve...