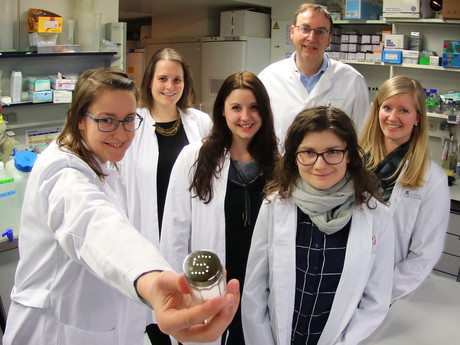

High-salt diet weakens the immune system

A high-salt diet is not only bad for one’s blood pressure, but also for the immune system. This is the conclusion of a study by German scientists, led by the University Hospital Bonn and published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that adults should consume no more than five grams of salt per day — approximately one level teaspoon — as sodium chloride is known to raise blood pressure and thereby increases the risk of heart attack or stroke. But figures from the Robert Koch Institute indicate that many Germans exceed this limit considerably, with men and women consuming an average of 10 and eight grams a day respectively.

Now, scientists have found another way in which salt is bad for us. As explained by Prof Dr Christian Kurts from the University of Bonn, “We have now been able to prove for the first time that excessive salt intake also significantly weakens an important arm of the immune system.”

This finding is unexpected, as some studies point in the opposite direction: for example, infections with certain skin parasites in laboratory animals heal significantly faster if these consume a high-salt diet. Macrophages, which are immune cells that attack, eat and digest parasites, are particularly active in the presence of salt. Several physicians concluded from this observation that sodium chloride has a generally immune-enhancing effect.

“Our results show that this generalisation is not accurate,” said lead author Dr Katarzyna Jobin, now at the University of Würzburg — and there are two reasons for this. Firstly, the body keeps the salt concentration in the blood and in the various organs largely constant — otherwise important biological processes would be impaired. The only major exception is the skin: it functions as a salt reservoir of the body, which is why the additional intake of sodium chloride works so well for some skin diseases.

However, other parts of the body are not exposed to the additional salt consumed with food. Instead, it is filtered out by the kidneys and excreted in the urine. This is where the second mechanism comes into play: the kidneys have a sodium chloride sensor that activates the salt excretion function. As an undesirable side effect, however, this sensor also causes so-called glucocorticoids to accumulate in the body. These in turn inhibit the function of granulocytes, the most common type of immune cell in the blood.

Granulocytes, like macrophages, are scavenger cells. However, they do not attack parasites, but mainly bacteria. If they do not do this to a sufficient degree, infections proceed much more severely.

“We were able to show this in mice with a listeria infection,” Dr Jobin said. “We had previously put some of them on a high-salt diet. In the spleen and liver of these animals we counted 100 to 1000 times the number of disease-causing pathogens.” Urinary tract infections also healed much more slowly in laboratory mice fed a high-salt diet.

Sodium chloride also appears to have a negative effect on the human immune system. As explained by Prof Kurts, “We examined volunteers who consumed six grams of salt in addition to their daily intake. This is roughly the amount contained in two fast food meals, ie, two burgers and two portions of French fries.”

After one week, the scientists took blood from their subjects and examined the granulocytes. The immune cells coped much worse with bacteria after the test subjects had started to eat a high-salt diet.

The excessive salt intake also resulted in increased glucocorticoid levels. That this inhibits the immune system is not surprising, according to the researchers: the best-known glucocorticoid cortisone is traditionally used to suppress inflammation.

“Only through investigations in an entire organism were we able to uncover the complex control circuits that lead from salt intake to this immunodeficiency,” Prof Kurts said. “Our work therefore also illustrates the limitations of experiments purely with cell cultures.”

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

Single-cell sequencing capability boosted in South Australia

The South Australian Genomics Centre has become the first certified service provider in...

Biomaterial helps to reverse aging in the heart

The discovery could open the door to therapies that rejuvenate the heart by changing its cellular...

mRNA used to force HIV out of hiding

Using the same technology behind mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, researchers have discovered a way to...