Inadequate T-cell development linked to autoimmune diseases

Researchers from Monash University have determined that mutations in the gene encoding a particular enzyme may help in the development of better treatments for a wide range of autoimmune diseases.

As part of their ongoing fundamental research program, scientists at the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute have built on previous research which had determined that the enzyme protein tyrosine phosphatase N2 (PTPN2) is associated with the development of rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s Disease, Type 1 diabetes, irritable bowel disease and other autoimmune diseases.

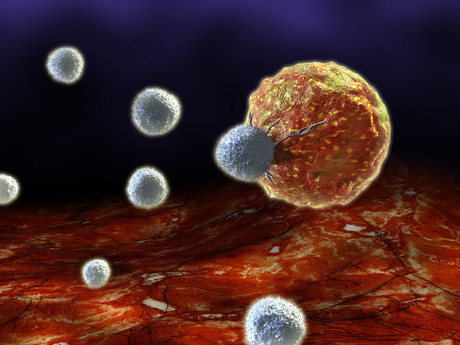

Their previous research had shown that decreased levels of PTPN2 is associated with T-cells turning on the body’s own cells and attacking healthy tissues. In this latest research, the scientists discovered that decreased levels of PTPN2 during a crucial phase in early T-cell development appears to have a causal link with the development of various autoimmune diseases.

The incidence of autoimmune diseases, particularly in the Western world, exceeds that of both cancer and heart disease. This broad spectrum of diseases is a leading cause of death and disability.

First author Dr Florian Wiede said this new research is “very exciting”, stating, “Understanding the mechanisms that govern early T-cell development and how these are altered in human disease may ultimately afford opportunities for novel treatments.”

Lead researcher Professor Tony Tiganis added, “This is an important advance in our understanding of critical checkpoints in T-cell development.”

During their research, the Monash team explored the roles of enzymes in early T-cell development and found that two particular T-cell subsets (αβ and γδ) were associated with different inflammatory and autoimmune conditions.

They found that the removal of the gene coding for PTPN2 led to the sort of pro-inflammatory properties associated with the development of autoimmune diseases. According to Professor Tiganis, “It helps decide whether the progenitors go on to become T-cells or something else; if they become one type of T-cell or another type.”

The Monash team also examined the specific pathways that are regulated by PTPN2. Professor Tiganis is optimistic about the potential clinical applications of this research.

“There are drugs that target some of these pathways — potentially we might be able to use existing drugs to target these pathways in the context of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases to help a subset of patients with a deficiency in this gene, although that is a long way off.”

Published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, this research was conducted at the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute, in collaboration with scientists from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and Peter Doherty Institute.

Breakthrough drug prevents long COVID symptoms in mice

Mice treated with the antiviral compound were protected from long-term brain and lung dysfunction...

Antibiotics hinder vaccine response in infants

Infants who received antibiotics in the first few weeks of life had significantly lower levels of...

Colossal announces 'de-extinction' of the dire wolf

Colossal Biosciences has announced what it describes as the rebirth of the dire wolf, which would...