Molecular blocker halts breast cancer metastasis

Through a combination of cellular biology and structural biology, researchers from Bar-Ilan University are advancing the fight against breast cancer in a way never before possible.

An estimated 90% of deaths from breast cancer are due to complications resulting from metastasis — a process in which cancer cells break away from where they first formed, travel through the blood or lymph circulatory system, and form new, metastatic tumours in other parts of the body. With no effective treatment to block this process, there is a need to target not only the primary tumour, but also its metastatic potential.

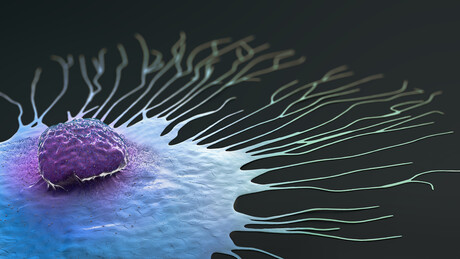

Cancer cells use feet-like protrusions called invadopodia to degrade underlying tissue, enter the bloodstream and form metastases in other organs. Approximately four years ago, Dr Hava Gil-Henn and colleagues revealed two important clues about the formation of invadopodia: the cellular level of the proteins Pyk2 and cortactin suspiciously increased when the cell entered its malignant phase, but when the cell lost its ability to produce Pyk2, no metastasis was observed whatsoever.

In a recent study expanding on this finding, Gil-Henn teamed up with Professor Jordan Chill to characterise the interaction between these partner proteins and showed that this interaction is a prerequisite for metastasis formation of cancer cells. Furthermore, they determined the mechanism in which the cortactin–Pyk2 interaction affects invadopodia formation and defined the structure of the complex between these two proteins. Their findings were published in the journal Oncogene.

The researchers defined the precise segment of the protein involved in the interaction between Pyk2 and cortactin. The small segment, known as a peptide, was synthesised in the laboratory and administered to breast cancer-bearing mice. The synthesised peptide successfully competed with the natural Pyk2 protein for the ‘attention’ of cortactin and essentially blocked Pyk2’s access to it. This inhibited the formation of the invadopodia and, as a result, the lungs of the mice remained much healthier, with very few, if any, metastases.

“We were very excited to see that the idea to use the Pyk2-binding motif to cortactin as an inhibitor for invadopodia worked in vivo quite well,” Gil-Henn said. “This served to prove the clinical potential of inhibiting the newly discovered interaction.”

All this was achieved using a very small segment of Pyk2, spanning only 19 of its 1009 amino acid building blocks; this was seen in the decrease in lung metastasis in the mouse model of breast cancer. In addition, it greatly reduced the invasiveness of breast tumour cells, stopped the maturation of invadopodia in tumour cells, and lowered the rate of polymerisation of actin, which is needed for progression in invadopodia formation. All these findings together provided unequivocal evidence that the 19-amino acid peptide actually blocks metastasis.

Chill noted, “The process of developing a successful drug from an inhibiting peptide is extremely demanding and is almost impossible to complete without a structural view of the complex between the peptide and its target, in this case cortactin.” Through an NMR experiment known as NOESY, the position of each of the 881 atoms of the cortactin protein and 315 atoms of the peptide was determined, creating a three-dimensional picture of the structure. The spatial position of the atoms is the secret to understanding the strength of the bond between the proteins, which is critical to creating a drug that will effectively prevent that bond. To illustrate this, it was found that amino acid #10 in the peptide fits exactly into the ‘slot’ in cortactin and must not be changed, while amino acid #11 faces outward and its exact identity is less important.

Gil-Henn and Chill are now focused on transforming the peptide into a better drug candidate, testing different sequences of amino acids to produce a product that will provide a stronger and more specific binding at the target site of cortactin. Specificity is crucial because the site in cortactin where the binding takes place, known as SH3, is similar to SH3 sites in other proteins, and any unwanted binding to another protein may cause side effects. Ultimately, the researchers hope their work will lead to the development of a drug that inhibits metastasis formation and improves survival chances and quality of life of patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer and other metastatic cancers.

Breakthrough drug prevents long COVID symptoms in mice

Mice treated with the antiviral compound were protected from long-term brain and lung dysfunction...

Antibiotics hinder vaccine response in infants

Infants who received antibiotics in the first few weeks of life had significantly lower levels of...

Colossal announces 'de-extinction' of the dire wolf

Colossal Biosciences has announced what it describes as the rebirth of the dire wolf, which would...