The missing link behind severe cases of COVID-19?

More than 10% of healthy people who develop severe COVID-19 have misguided antibodies that attack the patient’s own immune system, rather than the invading virus, with at least another 3.5% carrying genetic mutations that impair their immune response to the virus.

That’s according to the first results published out of the COVID Human Genetic Effort — an ongoing international project spanning over 50 sequencing hubs and hundreds of hospitals around the world. Co-led by Jean-Laurent Casanova from The Rockefeller University and Helen Su from the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the project may help explain why some people develop much more severe COVID-19 disease than others — particularly in patients who are otherwise young and healthy.

Genetics of COVID-19 outliers

The way SARS-CoV-2 affects people differently has been puzzling — the virus can cause a symptom-free infection and go away quietly, or it can kill in a few days. Casanova’s research over the past two decades has shown that unusual susceptibility to certain infectious diseases can be traced to single-gene mutations that affect an individual’s immune response.

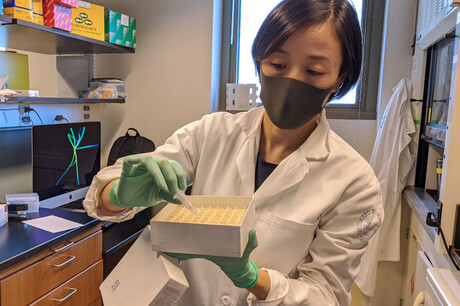

Since February, his team and their collaborators have been enrolling thousands of COVID-19 patients to find out whether something in their genetic make-up drives the disparate clinical outcomes the disease produces. Participants have covered various nationalities from Asia, Europe, Latin America and the Middle East, with study results published in two papers in the journal Science.

In one study, the researchers genetically analysed blood samples from more than 650 patients who had been hospitalised for life-threatening pneumonia due to SARS-CoV-2, 14% of whom had died. They also included samples from another group of over 530 people with asymptomatic or benign infection. They initially searched for differences between the two groups across 13 genes known to be critical for the body’s defence against the influenza virus. These genes govern the group of proteins known as type I interferons, which are part of our intrinsic and innate immunity, kicking in before the adaptive immune system mounts an antibody response.

It soon became obvious that a significant number of people with severe disease carried rare variants in these 13 genes, and more than 3% of them were in fact missing a functioning gene. Indeed, experiments showed that immune cells from these patients did not produce any detectable type I interferons in response to SARS-CoV-2. Follow-up experiments led by Rockefeller’s Charles M Rice showed that human fibroblast cells with mutations affecting the interferon type I pathway were more vulnerable to the virus, and died in higher numbers — and faster — than cells without those mutations.

A mysterious autoimmune condition

Three other infectious diseases caused by mutations affecting an immune signalling protein can also be caused by auto-antibodies against that protein, so the team also checked for the possibility of a similar scenario. Examining 987 patients with life-threatening COVID-19 pneumonia, they found that more than 10% had auto-antibodies against interferons at the onset of their infection. The vast majority of these (94%) were men, who tend to be more severely affected by COVID-19 than women.

Biochemical experiments confirmed these auto-antibodies can effectively curb the activity of interferon type I. In some cases, they could be detected in blood samples taken before patients became infected; in others, they were found in the early stages of the infection, before the immune system had the time to mount a response. They also appear to be rare in the general population; out of 1227 randomly selected healthy people, only four were found to have them.

“All of these findings strongly indicate that these auto-antibodies are actually the underlying reason some people get very sick, and not the consequence of the infection,” Casanova said.

So whether type I interferons have been neutralised by auto-antibodies, or were not produced in sufficient amounts in the first place due to a faulty gene, their being missing in action appears to be a common theme among severe COVID-19 sufferers.

“These findings provide compelling evidence that the disruption of type I interferon is often the cause of life-threatening COVID-19,” Casanova said.

The findings also point to certain medical interventions to consider for further investigation, Casanova claimed; for example, there are already two types of interferons available as drugs to treat certain conditions such as chronic viral hepatitis. In the meantime, the team continues to look for genetic variations that may affect other types of interferons or additional aspects of the immune response in COVID-19 outliers.

“COVID-19 may now be the best understood acute infectious disease in terms of having a molecular and genetic explanation for nearly 15% of critical cases across diverse ancestries,” Casanova concluded.

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

Heat-induced heart disease is killing Australians

Hot weather is responsible for an average of almost 50,000 years of healthy life lost to...

Call for greater diversity in genomics research

A gene variant common in Oceanian communities has been misclassified as a potential cause of...

Better semen quality linked to men living longer

Men with the best semen quality can expect to live two to three years longer, on average, than...