Wearable sweat sensor diagnoses cystic fibrosis

US researchers have developed a wristband-type sweat sensor that could transform diagnostics and drug evaluation for cystic fibrosis (CF), diabetes and other diseases. The sensor collects sweat, measures its molecular constituents and then electronically transmits the results for analysis and diagnostics.

Conventional methods for diagnosing cystic fibrosis — a genetic disease that causes mucus to build up in the lungs, pancreas and other organs — require that patients visit a specialised centre and sit still while electrodes stimulate sweat glands in their skin to provide sweat for the test. The electrodes can be annoying — especially for children, who have to sit still for 30 minutes while an instrument attached to their skin collects sweat. Even then, families have to wait while a lab measures the chloride ions in the sweat to determine if the child has cystic fibrosis.

Now, scientists at Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley have created a new type of sweat collector that does not require patients to sit still for a long time while sweat accumulates in the collectors. The senior authors on the study were Stanford’s Carlos Milla and Ronald Davis, who published the results in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

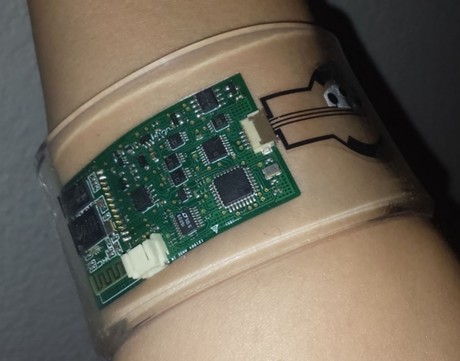

The two-part system of flexible sensors and microprocessors sticks to the skin, stimulates the sweat glands and detects the presence of different molecules and ions based on their electrical signals. The more chloride in the sweat, for example, the more electrical voltage is generated at the sensor’s surface. The team used the wearable sweat sensor in separate studies to detect chloride ion levels (high levels are an indicator of cystic fibrosis) and to compare levels of glucose in sweat to that in blood (high blood glucose levels can indicate diabetes).

The new method is much faster, quickly evaluating the contents of the sweat and beaming the data via a smartphone to a server that can analyse the results. The test happens all at once and in real time, noted Milla, making it much easier for families to have children evaluated.

Milla added that people living in underserved communities or developing countries could benefit from the portable, robust, self-contained sensor. CF diagnosis, as well as other kinds of diagnoses, could be done without needing a staff of skilled clinicians on duty and a well-equipped lab.

“You can get a reading anywhere in the world,” Milla said.

The sensor could also be used to help with drug development and drug personalisation, the researchers noted. As CF is caused by any of hundreds of different mutations in the CF gene, it’s possible to use the sensor to determine which drugs work best for which mutations.

“CF drugs work on only a fraction of patients,” said co-lead author Sam Emaminejad, now at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Just imagine if you use the wearable sweat sensor with people in clinical drug investigations — we could get a much better insight into how their chloride ions go up and down in response to a drug.”

In addition to measuring chloride ion and glucose levels, the technology can also be used to measure other molecular constituents of sweat, such as sodium and potassium ions and lactate. In fact, it can be used to measure virtually anything found in sweat.

“Sweat is hugely amenable to wearable applications and a rich source of information,” Davis said.

The team is now working on large-scale clinical studies to look for correlations between sweat-sensor readings and health. “In the longer term, we want to integrate it into a smartwatch format for broad population monitoring,” Emaminejad said.

Aspirin could prevent some cancers from spreading

The research could lead to the targeted use of aspirin to prevent the spread of susceptible types...

Heat-induced heart disease is killing Australians

Hot weather is responsible for an average of almost 50,000 years of healthy life lost to...

Call for greater diversity in genomics research

A gene variant common in Oceanian communities has been misclassified as a potential cause of...