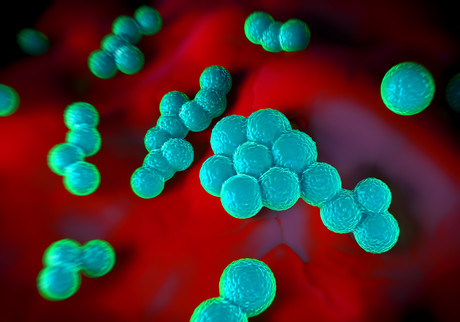

Antimicrobial polymers could help fight superbugs

Bacteria are becoming resistant to treatment faster than new antibiotics are being developed, causing experts to fear for the rise of the drug-resistant superbug. Now researchers from the University of South Australia (UniSA), as well as collaborators from The University of Melbourne, Monash University and CSIRO, may have found an effective treatment to combat this health challenge.

UniSA Research Fellow Dr Thomas Michl has been researching antimicrobial polymers, an up-and-coming new class of anti-infectives that can be used as an alternative to antibiotics. He stated, “For a long time, it was assumed that antimicrobial polymers worked the same way as antimicrobial peptides, so we put this theory to the test using high-resolution fluorescent microscopy.

“To our surprise, instead of just attacking the cell wall of the bacterium, as is the current understanding in the field, the polymers went into the bacterium.”

Building on previous work between UniSA and CSIRO, the team worked to create polymer mimics of antimicrobial peptides — a diverse class of naturally occurring molecules that act as the first line of defence for all multicellular organisms. With Dr Michl serving as lead author, their work has been published in the journal Acta Biomaterialia.

As peptides are easily broken down by the body, they don’t last long enough to be effective and are difficult to translate into new antibiotics. However, synthetic antimicrobial polymers can be made cheaply and easily on an industrial scale, and maintain their activity for longer periods in the body. Dr Michl said this makes them a promising lead for the development of a new type of antibiotic.

“The mechanism of how these polymers kill bacteria is more complicated than we first thought,” he said. “By understanding better how the polymers work, researchers can design them to be even more potent, opening up the potential for new and highly effective treatments for bacterial and fungal infections.”

Co-author Dr Katherine Locock, a senior research scientist at CSIRO, has already worked on translating these polymers into a novel thrush cream that may offer new hope for women who suffer from recurring thrush, for which treatment options are fairly restricted.

“There are currently only three classes of anti-fungals on the market, the last of which was discovered in the 1970s,” Dr Locock said.

“It turns out it is very difficult to come up with a new anti-fungal, given how closely related human and fungal cells are. The fact that we’ve managed to produce a whole new type of anti-fungal that is safe and effective in models of vaginal thrush is very exciting.”

Another exciting aspect of antimicrobial polymers is that they can be also used outside of health care, with Dr Michl noting, “There is scope to use antimicrobial polymers in any setting to suppress unwanted microbiological growth.

“One possibility, for example, would be as an alternative to fungicide to control mildew in plants, such as in vineyards or barley crops. Another opportunity would be in combating microbial infection in livestock.”

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

The University of Sydney formalises cervical cancer elimination partnership

The success of a cervical cancer elimination program has led to the signing of a memorandum of...

Noxopharm says paper reveals science behind its immune system platform

Clinical-stage Australian biotech company Noxopharm Limited says a Nature Immunology...

Neurosensing/neurostimulation implants session to be held on Monday

On Monday, a session at UNSW Sydney will include people who are benefiting from bioelectronics...