Bacteria can help the immune system destroy tumours

Introducing bacteria to a tumour’s microenvironment creates a state of acute inflammation that triggers the immune system’s primary responder cells to attack rather than protect a tumour, according to a study from the Garvan Institute of Medical Research.

The first-responder cells, called neutrophils, are white blood cells that play an important role in defence against infection. While they generally protect against disease, they are notorious for promoting tumour growth; high levels of them in the blood are typically associated with poorer outcomes in cancer, in part because they produce molecules that shield the tumour by suppressing the other elements of the immune system.

Garvan researchers, led by Dr Tatyana Chtanova, found that injecting inactivated Staphylococcus aureus microbes inside a tumour reverses that protective activity, stimulating the neutrophils to destroy the tumour in a range of animal cancer models, including Lewis lung carcinoma, triple-negative breast cancer, melanoma and pancreatic cancer.

“Using the immune system to fight cancer has been one of the biggest breakthroughs in cancer therapy in the last two decades, but currently immunotherapy for improving T cell function doesn’t work for all types of cancer,” Chtanova said. “We decided to use a different type of immunotherapy that targets neutrophils, to understand how generating acute inflammation in the immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment affects outcomes.”

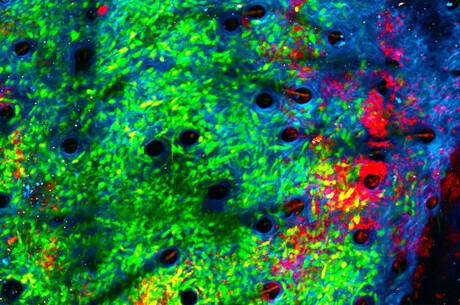

The team used intravital imaging in animal studies to see inside the tumours in real time. Chtanova explained, “Since attacking bacteria is the reason for neutrophils’ existence, we had a good inkling that introducing bacteria would bring neutrophils to the site and activate them. We discovered that it’s very effective in getting them to kill the tumours, chewing up their matrix.”

The team’s study, published in the journal Cancer Research, shows that the neutrophils also change at the gene expression level: they begin to secrete molecules that will attract fighter T cells as reinforcement.

“We’ve shown that microbial therapy is an effective booster for checkpoint inhibitor therapy, another type of cancer immunotherapy,” said Dr Andrew Yam, first author of the study. “We hope this synergistic effect will ultimately lead to better treatments to improve outcomes for patients with advanced or previously untreatable cancers.”

With the study having focused on primary tumours, the team will now spend the next 3–5 years developing their therapy to fight metastasis — the spread of cancer to other areas of the body — with clinical trials to follow.

TGA rejects Alzheimer's drug due to safety concerns

The TGA determined that the demonstrated efficacy of lecanemab in treating Alzheimer's did...

Defective sperm doubles pre-eclampsia risk in IVF patients

A high proportion of the father's spermatozoa possessing DNA strand breaks is associated with...

Free meningococcal B vaccines coming to the NT

The Northern Territory Government has confirmed the rollout of a free meningococcal B vaccine...