Bacteria tricked into opening pores in cell walls

UK scientists have developed a new technique to trick bacteria into revealing hundreds of holes in their cell walls, opening the door for drugs that destroy bacteria’s cells. Targeting these pores could make current antibiotics more effective or allow for the development of antibiotic-free drugs that can use these openings.

When subjected to certain stimuli, such as a dramatic increase of pressure inside the cell, pores in the cell membranes act like an emergency escape valve, opening up to allow liquid to flood out of the cell to prevent it from bursting. They act as the gateway to delivering treatments that destroy the bacteria’s cells. The largest of these gated pores is known as the mechanosensitive channel of large conductance (MscL).

Now a team led by Dr Christos Pliotas has learnt how to trick the bacterial cell walls into opening these channels, making the bacteria much more vulnerable to drugs. Dr Pliotas began this research while at the University of St Andrews, but has since relocated to the University of Leeds.

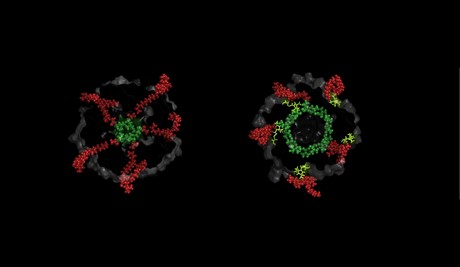

“Through understanding the gateways in the bacteria’s cell walls, we can then control their opening and closure,” Dr Pliotas said. “Simultaneous activation of these pores would result in the opening of 700 holes in the cell membrane (this is the number of identical such molecules per single cell), each ~3 nm in diameter.

“This would be the equivalent of shooting each cell with 700 bullets and 100% target efficiency, causing cell death due to leakage.

“Additionally, existing antibiotics should become more efficient by facilitating their access to the cell through MscL pores resulting in increased antibiotic concentration inside the cytoplasm.”

The study, published in the journal Nature Communications, shows for the first time that MscL channels are being kept closed by membrane lipids — specifically lipid chains — which are located within nano-pockets highly sensitive to tension, pressure and force. It demonstrates that when access of these lipids is disrupted by molecular nano-guards engineered at the entrance of the nano-pockets, the channel mechanically responds and opens its pore.

“This study used an emerging EPR method called PELDOR (or DEER),” said study co-author Dr Bela Bode, from the University of St Andrews. “We introduce tiny chemical markers on MscL and monitor changes in their distances. This has been instrumental for understanding the stimulus for opening of these complex biological systems.”

The MscL is ubiquitous in all bacterial pathogens and archaea, but absent from humans. Therefore, selective targeting of this channel would leave human cells intact.

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

Babies of stressed mothers likely to get their teeth earlier

Maternal stress during pregnancy can speed up the timing of teeth eruption, which may be an early...

Customised immune cells used to fight brain cancer

Researchers have developed CAR-T cells — ie, genetically modified immune cells manufactured...

Elevated blood protein levels predict mortality

Proteins that play key roles in the development of diseases such as cancer and inflammation may...