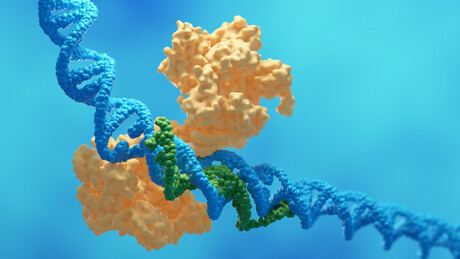

CRISPR molecular scissors can introduce genetic defects

CRISPR molecular scissors have the potential to revolutionise the treatment of genetic diseases, as they can be used to correct specific defective sections of the genome. Unfortunately, the repair can lead to new genetic defects when it comes to treating chronic granulomatous disease, as reported in the journal Communications Biology.

Chronic granulomatous disease is a rare hereditary disease that affects about one in 120,000 people. The disease impairs the immune system, making patients susceptible to serious and even life-threatening infections. It is caused by the absence of two letters, called bases, in the DNA sequence of the NCF1 gene. This error results in the inability to produce an enzyme complex that plays an important role in the immune defence against bacteria and moulds.

Researchers at the University of Zurich succeeded in using the CRISPR system to insert the missing letters in the right place, as demonstrated in cell cultures of immune cells that had the same genetic defect as people with chronic granulomatous disease. However, some of the repaired cells now showed new defects — entire sections of the chromosome where the repair had taken place were missing.

The reason for this is the special genetic constellation of the NCF1 gene: it is present three times on the same chromosome, once as an active gene and twice in the form of pseudogenes. These have the same sequence as the defective NCF1 and are not normally used to form the enzyme complex.

CRISPR molecular scissors cannot distinguish between the different versions of the gene and therefore occasionally cut the DNA strand at multiple locations on the chromosome — at the active NCF1 gene as well as at the pseudogenes. When the sections are subsequently re-joined, entire gene segments may be misaligned or missing. The medical consequences are unpredictable and, in the worst case, contribute to the development of leukaemia.

To minimise the risk, the team tested a number of alternative approaches, including modified versions of CRISPR components. They also looked at using protective elements that reduce the likelihood of the genetic scissors cutting the chromosome at multiple sites simultaneously. Unfortunately, none of these measures were able to completely prevent the unwanted side effects.

According to study co-author Professor Martin Jinek, the research provides valuable insights into the development of gene-editing therapies for chronic granulomatous disease and other inherited disorders. Ultimately, he concluded that further technological advances are needed to make the method safer and more effective in the future.

Novel antibiotic activates 'suicide' mechanism in superbug

Researchers have discovered a new class of antibiotic that selectively targets Neisseria...

Modifications in the placenta linked to psychiatric disorders

Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression disorder are the neuropsychiatric disorders...

ADHD may be linked with an increased risk of dementia

An adult brain affected by attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) presents modifications...