Early signs of immune response found in developing embryos

Researchers at Barcelona’s Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) have revealed that newly formed embryos clear dying cells to maximise their chances of survival, in what is said to be the earliest display of an innate immune response found in vertebrate animals to date. Their findings, published in the journal Nature, may aid future efforts to understand why some embryos fail to form in the earliest stages of development, and lead to new clinical efforts in treating infertility or early miscarriages.

Embryos are fragile in the first hours after their formation. Rapid cell division and environmental stress make them prone to cellular errors, which in turn cause the sporadic death of embryonic stem cells. This is assumed to be one of the major causes of embryonic developmental failure before implantation.

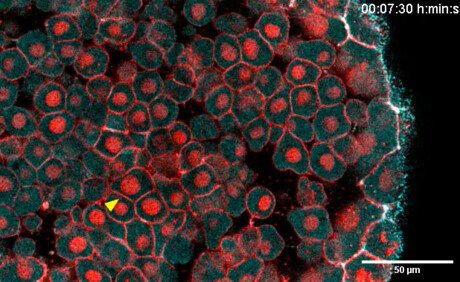

Living organisms can remove cellular errors using immune cells that are dedicated to carry out this function, but a newly formed embryo cannot create these specialised cells. To find out whether embryos can remove dying cells before the formation of an immune system, CRG researchers used high-resolution time-lapse imaging technology to monitor zebrafish and mouse embryos — two established scientific models used to study vertebrate development.

The researchers found that epithelial cells — which collectively form the first tissue on the surface of an embryo — can recognise, ingest and destroy defective cells. It is the first time this biological process, known as epithelial phagocytosis, has been shown to clear cellular errors in newly formed vertebrate embryos.

“Long before the formation of the organs, one of the first tasks performed by a developing embryo is to create a protective tissue,” said Dr Esteban Hoijman, first author on the paper. He added that epithelial phagocytosis was a surprisingly efficient process thanks to the presence of arm-like protrusions on the surface of epithelial cells.

“The cells cooperate mechanically; like people distributing food around the dining table before tucking into their meal, we found that epithelial cells push defective cells towards other epithelial cells, speeding up the removal of dying cells,” he said.

Dr Verena Ruprecht, senior author on the paper, said she and her team “propose a new evolutionarily conserved function for epithelia as efficient scavengers of dying cells in the earliest stages of vertebrate embryogenesis”, and that their work “may have important clinical applications by one day leading to improved screening methods and embryo quality assessment standards used in fertility clinics”.

The authors added that the discovery that embryos exhibit an immune response earlier than previously thought warrants further exploration on the role of mechanical cooperation as a physiological tissue function, which remains poorly understood, in other important biological processes such as homeostasis and tissue inflammation.

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

Babies of stressed mothers likely to get their teeth earlier

Maternal stress during pregnancy can speed up the timing of teeth eruption, which may be an early...

Customised immune cells used to fight brain cancer

Researchers have developed CAR-T cells — ie, genetically modified immune cells manufactured...

Elevated blood protein levels predict mortality

Proteins that play key roles in the development of diseases such as cancer and inflammation may...