Head injuries could be a risk factor for brain cancer

Studies have previously suggested a possible link between head injury and increased rates of brain tumours, but the evidence was inconclusive. UK researchers have now identified a possible mechanism to explain this link, implicating genetic mutations acting in concert with brain tissue inflammation to change the behaviour of cells, making them more likely to become cancerous. Their study has been published in the journal Current Biology.

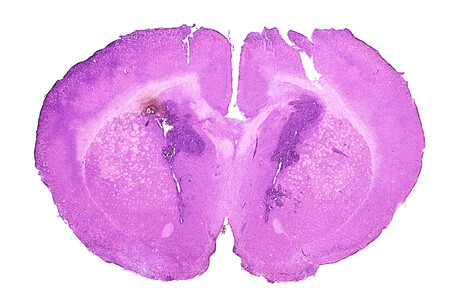

Gliomas are rare but aggressive brain tumours that often arise in neural stem cells. More mature types of brain cells, such as astrocytes, have been considered less likely to give rise to tumours; however, recent findings have demonstrated that after injury astrocytes can exhibit stem cell behaviour again. Professor Simona Parrinello, her team at University College London and their collaborators set out to investigate whether this property may make astrocytes able to form a tumour following brain trauma using a preclinical mouse model.

Young adult mice with brain injury were injected with a substance which permanently labelled astrocytes in red and knocked out the function of a gene called p53, known to have a vital role in suppressing many different cancers. A control group was treated the same way, but the p53 gene was left intact. A second group of mice was subjected to p53 inactivation in the absence of injury.

“Normally astrocytes are highly branched — they take their name from stars — but what we found was that without p53 and only after an injury the astrocytes had retracted their branches and become more rounded,” Parrinello said. “They weren’t quite stem cell-like, but something had changed. So we let the mice age, then looked at the cells again and saw that they had completely reverted to a stem-like state with markers of early glioma cells that could divide.”

This suggested that mutations in certain genes synergised with brain inflammation, which is induced by acute injury and then increases over time during the natural process of aging to make astrocytes more likely to initiate a cancer. Indeed, this process of change to stem cell-like behaviour accelerated when the researchers injected mice with a solution known to cause inflammation.

Looking to support their hypothesis in human populations, the team consulted electronic medical records of over 20,000 people who had been diagnosed with head injuries, comparing the rate of brain cancer with a control group. They found that patients who experienced a head injury were nearly four times more likely to develop a brain cancer later in life than those who had no head injury. That said, the risk of developing a brain cancer is overall low, estimated at less than 1% over a lifetime, so even after an injury the risk remains modest.

“We know that normal tissues carry many mutations which seem to just sit there and not have any major effects,” Parrinello said. “Our findings suggest that if on top of those mutations, an injury occurs, it creates a synergistic effect. In a young brain, basal inflammation is low so the mutations seem to be kept in check even after a serious brain injury. However, upon aging, our mouse work suggests that inflammation increases throughout the brain but more intensely at the site of the earlier injury. This may reach a certain threshold after which the mutation now begins to manifest itself.”

Novel antibiotic activates 'suicide' mechanism in superbug

Researchers have discovered a new class of antibiotic that selectively targets Neisseria...

Modifications in the placenta linked to psychiatric disorders

Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression disorder are the neuropsychiatric disorders...

ADHD may be linked with an increased risk of dementia

An adult brain affected by attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) presents modifications...