How cells remember their identity

Cancer is often the result of DNA mutations or problems with how cells divide, which can lead to cells ‘forgetting’ what type of cell they are or how to function properly. Now scientists at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies have provided clarity into how new cells remember their identity after cell division — which could explain how problems occur when cell identity is not maintained. Their work has been published in the journal Genes & Development.

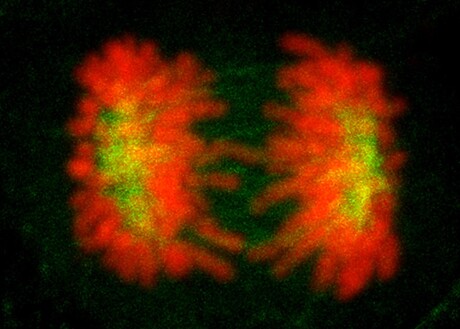

Cell division is one of the most critical periods of tissue development and homeostasis. During this process, called mitosis, cells have to copy all their DNA correctly and then split evenly in two.

To reduce distractions, gene activity turns off during mitosis, right before the cells divide, stopping the production of proteins. After the cell divides into two cells, gene expression turns back on, in a coordinated fashion, to restart protein production. This process of starting up the production of specific proteins informs the cell of what it should become, yet scientists did not previously know how exactly this process worked.

“We wanted to understand the molecular mechanisms of cell identity and transcriptional memory,” said Hyeseon Kang, first author of the paper. “How does the mother cell pass on identity to the daughter cells through cell division?”

Under normal conditions, cultured cells in the laboratory are at multiple stages of the cell cycle. This makes it difficult to pinpoint the time period right after mitosis when the cells are remembering what type of cell to become. The researchers synchronised retinal cells and bone cancer cells using a chemical inhibitor, which aligned them to the same stage of the cell life cycle. The scientists were then able to examine the short window when genes are active after mitosis. This technique provides a complete picture of the reactivation of the cell’s entire genome after mitosis, for the first time.

The team found that many genes are activated immediately after cell division. The genes act in a cascade, like a row of falling dominos, to send critical signals to activate additional genes. This process of activation allows the cell to ‘wake up’ from its cellular amnesia and become its destined identity.

“This research focuses on a fundamental question: how does a cell remember who it is and what it’s supposed to be doing?” said study co-author Jesse Dixon. “We have mapped out when and where a lot of these memory features are established. Next, we can start to manipulate specific features to gain a better mechanistic understanding of cell identity.”

“We gained new insights into the memory mechanisms that allow the right genes to turn on at the right time, so that a new cell can become the same type of cell as the parent cell,” said Professor Martin Hetzer, senior author of the paper. “Our findings lay the foundation for understanding this brief and dynamic cell life stage that is critical for cellular identity.”

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

Babies of stressed mothers likely to get their teeth earlier

Maternal stress during pregnancy can speed up the timing of teeth eruption, which may be an early...

Customised immune cells used to fight brain cancer

Researchers have developed CAR-T cells — ie, genetically modified immune cells manufactured...

Elevated blood protein levels predict mortality

Proteins that play key roles in the development of diseases such as cancer and inflammation may...