Immune cells move more independently than we thought

Researchers at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) have discovered that immune cells do not just passively follow chemical cues in order to reach their target. In fact, they are capable of shaping these cues and navigating complex environments in a self-organised manner.

Directional cell movement is an essential and fundamental phenomenon of life — an important prerequisite for individual development, reformation of blood vessels and immune response, among others. Chemokines, a class of signalling proteins, play a crucial role in guiding immune cells to specific locations; they are formed in the lymph nodes and create chemical cues called chemokine gradients for cells to follow within the body. According to researcher Jonna Alanko, these chemokine gradients are like a trail of scent left in the air that gets lighter the further you are from its source.

The traditional idea has been that immune cells recognise their target by following existing chemokine gradients; in other words, the cells following these cues have been seen as passive actors. But as explained by Alanko, “We were able to prove for the first time that, contrary to the previous conception, immune cells do not need an existing chemokine gradient to find their way. They can create gradients themselves and thereby migrate collectively and efficiently even in complex environments.”

Immune cells have receptors with which they can sense a chemokine signal. One of these receptors is called CCR7 and can be found in dendritic cells — professional antigen-presenting cells with an important role in activating the entire immune response. They need to locate an infection, recognise it and then migrate to the lymph nodes with the information. In the lymph nodes, the dendritic cells interact with other cells of the immune system to initiate an immune response against pathogens.

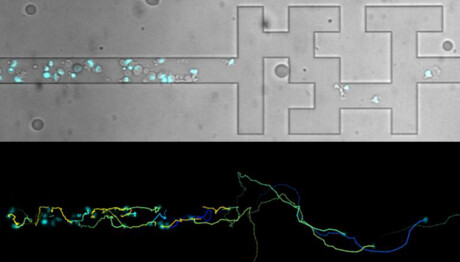

Alanko’s study revealed that dendritic cells not only register a chemokine signal with their CCR7 receptor, they also actively shape their chemical environment by consuming chemokines. By doing this, the cells create local gradients that guide their own movement and that of other immune cells. The researchers also discovered that T cells, another type of an immune cell, can benefit from these self-generated gradients to enhance their own directional movement.

“When immune cells are capable of creating chemokine gradients, they can avoid upcoming obstacles in complex environments and guide their own directional movement and that of other immune cells,” Alanko said.

The discovery, which was published in the journal Science Immunology, increases our understanding of how immune responses are coordinated within the body. It can also reveal how cancer cells guide their movement to create metastases.

“The CCR7 receptor has also been discovered in many cancer types and in these cases, the receptor has been seen to boost cancer metastasis,” Alanko said. “Cancer cells may even use the same mechanism as immune cells to guide their movement. Therefore, our findings may help design new strategies to modify immune responses as well as to target certain cancers.”

Damaged RNA, not DNA, revealed as main cause of acute sunburn

Sunburn has traditionally been attributed to UV-induced DNA damage, but it turns out that this is...

Multi-ethnic studies identify new genes for depression

Two international studies have revealed hundreds of previously unknown genetic links to...

Oxygen deprivation may contribute to male infertility

Medical conditions that deprive the testes of oxygen, such as sleep apnoea, may be contributing...