New immune cell in skin

Researchers at the Centenary Institute in Sydney, SA Pathology in Adelaide, and the Malaghan Institute in Wellington, New Zealand and the USA have identified a new subset of group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) in the skin of mice.

The cells, which were discovered less than five years ago in the gut and the lung and linked to asthma, are phenotypically unique and abundant in skin.

“Our data show that these skin ILC2 cells can likely suppress or stimulate inflammation under different conditions,” said Dr Ben Roediger, research officer in the Immune Imaging Laboratory at the Centenary Institute headed by Professor Wolfgang Weninger. “They also suggest a potential link to allergic skin diseases.”

Allergies and eczema are debilitating skin conditions that affect hundreds of millions of people worldwide. The researchers hope that dermal ILC2 cells will provide some insights into the causes of these diseases.

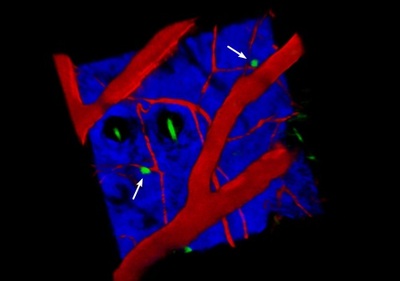

Weninger’s lab has developed sophisticated live imaging techniques for marking different cells and tracking them under the microscope.

The team actually discovered the dermal ILC2 cells some years ago, “We just didn’t know what they were,” Roediger said.

The researchers, however, suspected they might be associated with type 2 immunity - that part of the immune system critical for defence against parasitic infections and also underlying the development of allergic skin diseases - so they contacted Professor Graham Le Gros at the Malaghan Institute, one of the world’s foremost researchers into type 2 immunity.

Le Gros and his team confirmed the cells were a new member of the ILC2 family and provided a new strain of mouse developed in the USA that gave further insight into the function of these cells.

The researchers found the ILC2 cells were the major population in the skin of these mice that produced interleukin 13, a cytokine that is a critical regulator of the allergic response. Interleukin 13 has been linked to a number of allergic diseases, including eczema.

Using intravital multiphoton microscopy, the Centenary researchers watched the behaviour of the ILC2 cells in the skin. The cells moved in a characteristic way - in random spurts punctuated by stoppages.

“A halt in movement usually indicates some sort of interaction with another cell,” Roediger said. In this case, the ILC2 cells stopped in close proximity to mast cells, which play a key role in controlling parasitic infections and are associated with allergies. In addition, mast cell function was suppressed by IL-13.

As well as the interaction with mast cells, the ILC2 cells could be stimulated to spread quickly and were capable of generating inflammatory skin disease.

The research was recently published in the respected journal Nature Immunology.

Farm animals and aquaculture cryopreservation partnership announced

Vitrafy Life Sciences Limited has announced that it has entered a 12-month exclusive agreement...

Babies of stressed mothers likely to get their teeth earlier

Maternal stress during pregnancy can speed up the timing of teeth eruption, which may be an early...

Customised immune cells used to fight brain cancer

Researchers have developed CAR-T cells — ie, genetically modified immune cells manufactured...