Researchers find a way to improve immune response

Melbourne researchers have identified a way to improve the immune response in the face of severe viral infections, revealing their results in the journal Immunity.

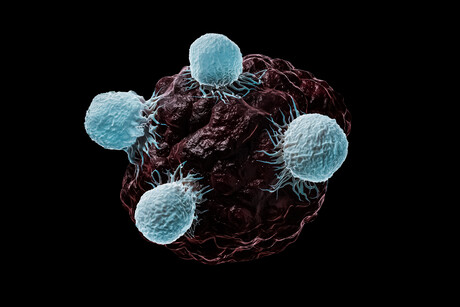

It is widely known that severe viral infections and cancer cause impairments to the immune system, including to T cells — a process called immune exhaustion. Overcoming immune exhaustion is a major goal for the development of new therapies for cancer or severe viral infections. Researchers from The Peter Doherty Institute of Infection and Immunity, led by The University of Melbourne’s Dr Sarah Gabriel, Dr Daniel Utzschneider and Professor Axel Kallies, have now been able to identify why immune exhaustion occurs and how this may be overcome.

“This idea that you need to overcome exhaustion and make T cells better is at the heart of immunotherapy,” Prof Kallies said.

“While immunotherapy works really well, it is only effective in around 30% of people. By discovering a way to prime T cells differently so they can work efficiently in the long run, we may be able to make immunotherapy more effective in more people.”

The team had previously identified that while some T cells lost their function and became exhausted within days, others, called Tpex cells, were able to maintain their function for a long period of time. Now, the team has identified a mechanism explaining how Tpex cells can maintain their fitness over long periods — a discovery that has the potential to improve the success rate of immunotherapy.

“We found that activity of mTOR, a nutrient sensor that coordinates cellular energy production and expenditure, is reduced in Tpex cells compared to those which were becoming exhausted,” Dr Gabriel said.

“What this means is that Tpex cells were able to dampen their activity so they could remain functional longer. It’s like going slower to have the endurance to run a marathon instead of a sprint at full speed.”

Dr Utzschneider stressed that flicking this switch to the immune system is a balancing act, saying, “You don’t want to dampen the response too much to the point the response becomes ineffective — you don’t want to be left walking the race.

“The next step was finding the mechanism which was enabling this. We discovered that Tpex cells were exposed to increased amounts of an immunosuppressive molecule, TGFb, early on in an infection. This molecule essentially acts as a brake, reducing the activity of mTOR and thereby dampening the immune response.”

The researchers were able to use this discovery to improve the immune response to severe viral infection, with Dr Gabriel revealing, “When we treated mice with an mTOR inhibitor early, this resulted in a better immune response later during the infection.

“In addition, mice that had been treated with the mTOR inhibitor responded better to checkpoint inhibition, a therapy widely used in cancer patients.”

The team will now explore this mechanism in preclinical cancer models.

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

AusBiotech and Proto Axiom partner on investor-focused life sciences programs

AusBiotech and Proto Axiom have announced a partnership to strengthen national coordination...

The University of Sydney formalises cervical cancer elimination partnership

The success of a cervical cancer elimination program has led to the signing of a memorandum of...

Noxopharm says paper reveals science behind its immune system platform

Clinical-stage Australian biotech company Noxopharm Limited says a Nature Immunology...