Viruses used as 'vehicles' to deliver cancer vaccines

An international research group led by the University of Basel has developed a promising strategy for therapeutic cancer vaccines. Using two different viruses as vehicles, they administered specific tumour components into mice with cancer in order to stimulate their immune system to attack the tumour.

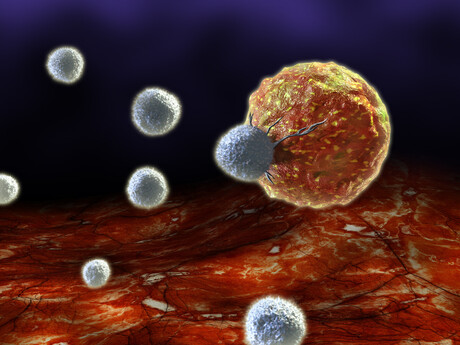

Making use of the immune system as an ally in the fight against cancer forms the basis of a wide range of modern cancer therapies, including therapeutic cancer vaccination. Following diagnosis, specialists set about determining which components of the tumour could function as an identifying feature for the immune system. The patient is then administered exactly these components by means of vaccination, with a view to triggering the strongest possible immune response against the tumour.

Viruses that have been rendered harmless are used as vehicles for delivering the characteristic tumour molecules into the body. In the past, however, many attempts at creating this kind of cancer therapy failed due to an insufficient immune response. One of the hurdles is that the tumour is made up of the body’s own cells, and the immune system takes safety precautions in order to avoid attacking such cells. In addition, the immune cells often end up attacking the ‘foreign’ virus vehicle more aggressively than the body’s own cargo.

Professor Daniel Pinschewer and his research group at Basel had already discovered in previous studies that viruses from the arenavirus family are highly suitable as vehicles for triggering a strong immune response. With this in mind, they conducted animal experiments using a combination of two different arenaviruses, reporting their results in the journal Cell Reports Medicine.

The researchers focused on two distantly related viruses — Pichinde virus and Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus — which they adapted via molecular biological methods for use as vaccine vectors. When they administered the selected tumour component first with the one virus and then, at a later point, with the other, the immune system shifted its attack away from the vehicle and more towards the cargo.

“By using two different viruses, one after the other, we focus the triggered immune response on the actual target, the tumour molecule,” said Prof Pinschewer.

In experiments with mice, the researchers were able to measure a potent activation of killer T cells that eliminated the cancer cells. In 20–40% of the animals — depending on the type of cancer — the tumour disappeared, while in other cases the rate of tumour growth was at least temporarily slowed.

“We can’t say anything about the efficacy of our approach in humans as yet,” Prof Pinschewer noted, as the effects on tumours in animal experiments cannot be assumed to translate directly into the effect on corresponding cancer types in humans. “However, since the therapy with two different viruses works better in mice than the therapy with only one virus, our research results make me optimistic.”

Biotech company Hookipa Pharma, of which Prof Pinschewer is one of the founders, is now investigating the efficacy of this novel approach to cancer therapy in humans. “If it proves successful,” he said, “a wide range of combinations with existing therapies could be envisaged, in which the respective mechanisms would join forces to eliminate tumours even better.”

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

Cannabis use may double risk of cardiovascular disease death

Cannabis users have a 29% higher risk of acute coronary syndrome, a 20% higher risk of stroke,...

Space conditions can lead to periodontitis, scientists say

Living in zero gravity can lead to periodontitis — a serious condition where the gums...

Personalised brain stimulation helps treat those with depression

By tailoring transcranial magnetic stimulation to each person's unique brain structure,...