Faster, safer method for producing stem cells

A new method for generating stem cells from mature cells promises to boost stem cell production in the laboratory, helping to remove a barrier to regenerative medicine therapies that would replace damaged or unhealthy body tissues.

A new method for generating stem cells from mature cells promises to boost stem cell production in the laboratory, helping to remove a barrier to regenerative medicine therapies that would replace damaged or unhealthy body tissues.

The technique, developed by researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, allows for the unlimited production of stem cells and their derivatives as well as reduces production time by more than half, from nearly two months to two weeks.

“One of the barriers that needs to be overcome before stem cell therapies can be widely adopted is the difficulty of producing enough cells quickly enough for acute clinical application,” said Ignacio Sancho-Martinez, one of the first authors of the paper and a postdoctoral researcher in the laboratory of Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, the Roger Guillemin Chair at the Salk Institute.

They and their colleagues, including Fred H Gage, a professor in Salk’s Laboratory of Genetics, have published a new method for converting cells in Nature Methods.

Stem cells are valued for their ‘pluripotency’ - the ability to become nearly any cell in the body. Stem cells for research and clinical uses are derived in two ways - either directly from cells young enough to still be pluripotent or from mature cells that have been ‘reprogrammed’ to be pluripotent.

The first kind are called ‘embryonic stem cells’ (ESCs), even though the term is a misnomer. They are actually taken from blastocysts, the hollow bundle of cells approximately the size of a tip of a pin that is formed by a fertilised egg after five days of cell division. After a blastocyst implants in the uterus, the embryo stage begins.

Aside from the ethical controversies, ESCs have a less discussed problem: tissues grown from ESCs may trigger immune reactions when they are transplanted into patients.

In order to overcome both ethical and medical concerns, scientists learned how to coax mature cells (called ‘somatic cells’) that had differentiated into particular types of tissue back to their pluripotent state. These so-called ‘induced pluripotent stem cells’ (iPSCs) set off whole new rounds of research, including a third way to get desired cell types.

As it turns out, iPSCs have their own problems. They take a long time to create in the lab, in a highly inefficient process that can take up to two months to complete. First, somatic cells must be reprogrammed to iPSCs, which takes considerable time and effort. Then, the iPSCs have to be differentiated into specific cell lineages prior to therapeutic application. Far worse, they can sometimes develop into tumours, called teratomas, which can be cancerous.

Knowing this, scientists wondered if it might not be necessary to go all the way back to the blank slate of a pluripotent stem cell. Key to this idea is that pluripotent stem cells do not immediately grow into particular cells. They go through intermediate progenitor phases where they become ‘multipotent’, and can only develop into cell types within a certain cellular lineage. While a pluripotent cell can become nearly any cell in the body, a multipotent blood cell, for example, can become red or white blood cells or platelets, but not distant lineages such as neurons.

Thus, in order to avoid the potential problems of working with iPSCs, scientists developed the technique of ‘direct lineage conversion’. Unlike the familiar scenario in which a pluripotent cell would divide and generate all different cell types of an adult individual, in direct lineage conversion one somatic cell is turned into just one other cell type; for example, one skin cell becomes one muscle cell, but nothing else.

While this technique is effective, the Salk team and their colleagues wondered if there might be a modification that could be both more efficient and safer.

“Beyond the obvious issue of safety, the biggest consideration when thinking about stem cells for clinical use is productivity,” said Salk postdoctoral researcher Leo Kurian, a first co-author on the paper.

The team developed a new technique, which they dubbed ‘indirect lineage conversion’ (ILC). In ILC, somatic cells are pushed back to an earlier state suitable for further specification into progenitor cells.

ILC has the potential to generate multiple lineages once cells are transferred to the team’s specially developed chemical environment. Most importantly, ILC saves time and reduces the risk of teratomas by not requiring iPSC generation. Instead, somatic cells are directed to become the progenitor cells of particular lineages. “We don’t push them to zero, we just push them a bit back,” Sancho-Martinez said.

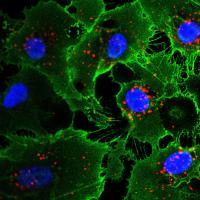

Using ILC, the group reprogrammed human fibroblasts (skin cells) to become angioblast-like cells, the progenitors of vascular cells. These new cells could not only proliferate, but also further differentiate into endothelial and smooth muscle vascular lineages. When implanted in mice, these cells integrated into the animals’ existing vasculature.

“One of the long-term hopes for stem cell research is exemplified by this study, where stem cells would self-assemble into 3D structures and then integrate into existing tissues,” said Izpisua Belmonte.

While such clinical use may be years away, this new method has several advantages over current techniques, he explains. It is safer, since it does not seem to produce tumours or other undesirable genetic changes, and results in much greater yield than other methods. Most important, it is faster, and this is part of what makes it not only more productive, but less risky.

“Generally it can take up to two months to create iPSCs and their differentiated derivatives, which increases the chances for mutations to take place,” said Emmanuel Nivet, the third of the first co-authors. “Our method takes only 15 days, so we’ve substantially decreased the chances for spontaneous mutations to take place.”

Solar-powered reactor uses CO2 to make sustainable fuel

Researchers have developed a reactor that pulls carbon dioxide directly from the air and converts...

Scientists simulate the effects of an asteroid collision

How would our planet physically react to a future asteroid strike? Researchers simulated an...

2024 was warmest year on record, 1.55°C above pre-industrial level

The World Meteorological Organization says that 2024 was the warmest year on record, according to...