Predicting and detecting metastasis in prostate cancer

Two new studies from US researchers are helping to differentiate the subset of prostate cancer patients who require more aggressive management and treatment — one detecting the disease through a simple and inexpensive device and the other revealing a biomarker that predicts metastasis before it even occurs.

For about 90% of men with prostate cancer, the cancer remains localised to the primary site, resulting in a five-year survival rate of almost 100%. Unfortunately, the remaining 10% of patients develop locally invasive and metastatic disease, which increases the severity of the disease and likelihood of death, and limits treatment options.

“Predicting aggressive behaviour in prostate cancer is an entirely unmet and urgent need,” said Marie E Robert, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine. “There are currently no tissue-based biomarkers to help clinicians reliably identify the subset of prostate cancer patients who will progress to life-threatening, disseminated disease and who would, therefore, benefit from systemic therapies before or following prostatectomy.”

Robert and her colleagues have revealed that a significantly lower presence of syntaphilin (SNPH) — a mitochondrial protein — within a tumour’s central core, versus at the tumour’s invasive outer edge, may identify patients at increased risk of metastasis. Their work has been published in The American Journal of Pathology.

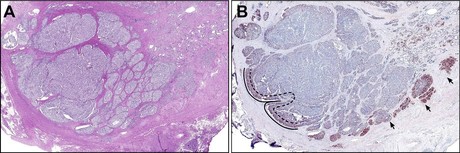

Investigators found that SNPH — a key determinant of the balance between tumour cell proliferation and tumour cell invasion — is abundantly expressed in prostate cancer, where it exhibits high expression at the invasive tumour edge compared to the central tumour bulk, correlating with greater cell proliferation at the tumour edge location. They also found that SNPH expression increases with increasing Gleason pattern. Of potential vital clinical relevance, low central tumour expression correlated with an increased risk of metastasis in a group of patients undergoing radical prostatectomy.

The investigators analysed tissue specimens from 89 men with prostate adenocarcinoma who had undergone removal of the prostate. They found that SNPH manifests a unique, biphasic spatial distribution in prostate tumours, meaning that in 96% of the prostate cancer tumours analysed, SNPH levels were elevated at the outer invasive edge where it correlates with increased tumour cell proliferation, but decreased within the central tumour core. This differential was more pronounced in more advanced tumours.

Importantly, central tumour SNPH measures (H scores) were significantly lower in 16 patients with metastases compared to patients without metastases, whereas SNPH scores at the invasive edges were not different in patients with or without metastases. Most of the metastases also expressed SNPH strongly. The researchers suggest that SNPH acts as a negative regulator of mitochondrial activity and that its down-regulation in the central portions of primary prostate cancer is associated with an increased risk of metastatic disease.

“This is the first study to suggest a clinical role for SNPH assessment in prostate cancer prognosis, potentially confirming recent evidence in experimental models of its importance in the phenotypic switch between proliferative and metastatic tumour states,” Dr Robert said. “Our results also reaffirm a critical, emerging role of mitochondrial biology in influencing tumour behaviour.

“If our findings are supported by larger studies, SNPH measurement in tumours could be developed into a predictive biomarker.”

There is also a great need for better screening in those whose prostate cancer has already metastasised. Men over 50 are urged to have an annual test for prostate specific antigen (PSA), but this test will not detect metastatic cancer. And treatment of early-stage cancers is often done by suppressing testosterone or through ablation, where extreme heat or cold are used to destroy tumours — but most prostate tumour cells that survive this treatment become metastatic.

Now, researchers from Texas Tech University have developed a device that forces cell samples through tiny channels less than 10 µm wide. When prostate cancer cells are forced through these channels, the metastatic cells exhibit ‘blebbing’, in which portions of the cell’s outer layer bulges outward from the more rigid inner layer. The resulting bulges, known as blebs, allow the cell to migrate the way amoeba do. This crawling-type motion is accomplished when the cell sends out cytoplasm protrusions known as pseudopodia, or ‘false feet’.

In tests with their new microchannel instrument, the investigators observed that highly metastatic prostate cancer cells exhibited more blebbing in the channel than did moderately metastatic or normal cells. 56% of the highly metastatic cells produced blebs, whereas only 29% of normal cells and only 38% of moderately metastatic cells did. Further studies revealed that a low amount of the protein F-actin in the cell’s cytoplasm may cause blebbing by providing fewer binding sites for other proteins that normally anchor the cell’s plasma membrane to the inner cortex.

Described in the journal Biomicrofluidics, the new device can quickly detect the amount of blebbing in cells from cancer samples and could potentially be used in a clinical setting to inexpensively test large numbers of samples. It could thus provide a simple and inexpensive diagnostic method for metastatic cancer, according to study co-author Fazle Hussain.

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

Solar-powered reactor uses CO2 to make sustainable fuel

Researchers have developed a reactor that pulls carbon dioxide directly from the air and converts...

Scientists simulate the effects of an asteroid collision

How would our planet physically react to a future asteroid strike? Researchers simulated an...

2024 was warmest year on record, 1.55°C above pre-industrial level

The World Meteorological Organization says that 2024 was the warmest year on record, according to...