We could grow jet fuel on gum trees — if there's anywhere left to plant them

Scientists are one step closer to using Australia’s iconic gum trees to develop low-carbon renewable jet and missile fuel. The only problem is, the habitat of more than 90% of eucalypt species is set to decline in the near future due to climate change.

Researchers from The Australian National University (ANU) participated in an international study which set out to find an alternative to fossil fuels for the aviation industry. As explained by Dr Carsten Kulheim, powering a modern jet aircraft with anything other than fossil fuels is difficult due to the high energy required.

“Renewable ethanol and biodiesel might be okay for the family SUV, but they just don’t have a high enough energy density to be used in the aviation industry,” he said.

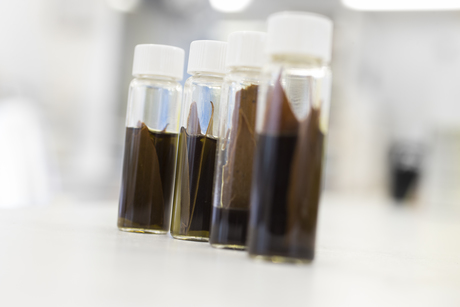

The good news, said Dr Kulheim, is that eucalyptus oil contains compounds called monoterpenes, which can be refined through a catalytic process and converted into a very high-energy fuel. Co-researcher David Kainer added that jet fuel derived from eucalyptus oils would be close to carbon neutral, saying, it would have “minimal ecological impact”.

“We can plant these trees on marginal lands that have low rainfall, and we can also plant them in agricultural systems that have salinity problems and help them defeat that problem,” he said.

Writing in the journal Trends in Biotechnology, the researchers examined how to boost production of monoterpenes to obtain industrial scales of jet fuel from plants. This includes selecting appropriate species, genetic analysis, advanced molecular breeding, genetic engineering and improvements to harvesting/processing of the oils.

“We’re looking for species that have the right type of oil and in addition to that, since the oil is in the leaves, they need to grow a lot of leaves in a short amount of time,” said Kainer.

“Eucalyptus plantations globally produce up to 200 kg of oil per hectare per year, but by selecting the best genetic stock they could produce more than 500 kg of oil per hectare.”

“If we could plant 20 million hectares of eucalyptus species worldwide, which is currently the same amount that is planted for pulp and paper, we would be able to produce enough jet fuel for 5% of the aviation industry,” Dr Kulheim added.

There’s just one hitch in the plan — a separate international study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, has found that Australians could see fewer suitable environments for the country’s iconic eucalypt trees within a generation, with 16 species forecast to lose their home environments entirely within 60 years.

Researchers from the University of Melbourne, Dr Laura Pollock and Dr Heini Kujala, used over 260,000 geospatial data points from eucalypt specimens stored in Australia herbaria and accessed through Australia’s Virtual Herbarium. This information was used to create models of current locations and preferred environmental conditions for 657 species of eucalypt trees.

“Once we had developed the models, we could then determine which areas in Australia would be climatically suitable for the species in the future, as the climate changes,” Dr Kujala said.

Associate Professor Bernd Gruber, of the University of Canberra, said a 3°C temperature rise over the next 60 years will see a decline of suitable habitat for 91% of the 657 species of eucalypts studied.

“As a consequence, the distribution of many species will change, and we expect trees suited to temperate and southern Australia to be hit particularly hard, contracting to more climatically suitable areas further south or at higher elevations,” he said.

The research found that rare, evolutionarily ancient trees which have existed for a long time will feel the brunt of climate change, with Associate Professor Gruber saying, “At least 16 species would have suitable climatic zones disappear altogether.

“Our analysis suggests that only 9% of eucalypt species have the potential to increase their distribution over the same time period.”

Associate Professor Gruber said the study “demonstrates the importance of not simply counting the number of species in biodiversity conservation, but also considering their evolutionary history, which determines how closely related species are to each other”.

“Using this approach we were able to identify hotspots that will contain high levels of eucalypt diversity under a changing climate, both in terms of the number of species and their reflection of the trees’ evolutionary pathways. Protecting these hotspots will be important to ensure we retain biodiversity in the future,” he said.

European Space Agency inaugurates deep space antenna in WA

The ESA has expanded its capability to communicate with scientific, exploration and space safety...

Black hole collision supports Hawking's landmark theory

Astrophysicists have witnessed a collision between two black holes that was so loud, they were...

Uncovering differences in wild and domesticated crops

Researchers have revealed insights into the genetic make-up of wild varieties of common crops...