Gene study finds humans helped drive golden staph's success

Humans have been identified as the original hosts for the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus, commonly known as golden staph, according to an international study.

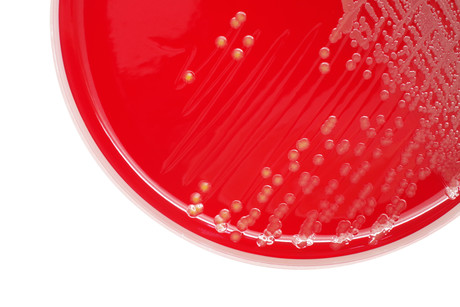

S. aureus bacteria usually live harmlessly in our noses. If the bacteria get into a cut, however, they can cause infections that, in rare instances, can be deadly.

Antibiotic-resistant strains of the bacteria, such as MRSA, are a major cause of hospital-acquired infections. The bacteria is also a major burden for the agricultural industry, as it causes diseases such as mastitis in cows and skeletal infections in broiler chickens.

An international research team, led by the University of Edinburgh’s Roslin Institute, sought to investigate the evolutionary history of the bacteria and key events that had allowed it to jump between species. In order to do this, they analysed the entire genetic make-up of more than 800 strains of S. aureus that were isolated from people and animals.

Writing in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, the researchers revealed that humans were likely the original hosts for the bacteria, with the first strains capable of infecting livestock emerging around the time animals were first domesticated for farming. Human interactions with livestock thus provided opportunities for the bugs to switch hosts, jumping between cows and humans. Cows have been a source of strains that now cause infections in human populations worldwide, the study found.

The study also found that industrialised agriculture, including the use of antibiotics and feed supplements in intensive farming, has directly influenced the evolution of golden staph, leading to antibiotic resistance. Furthermore, each time the bacteria jumps species, it acquires new genes that enable it to survive in its new host; genes that in some cases confer resistance to commonly used antibiotics.

Genes linked to antibiotic resistance are unevenly distributed among strains that infect humans compared with those that infect animals, the study found. The researchers say this reflects the distinct practices linked to antibiotic usage in medicine and agriculture.

Investigating how the bacteria are affected by genetic changes that occur after it jumps species could reveal opportunities to develop new antibacterial therapies, the researchers say. It could also help to inform better strategies for managing infections to reduce the risk of transmission to people, and slow the emergence of antibiotic resistance.

“Our findings provide a framework to understand how some bacteria can cause disease in both humans and animals, and could ultimately reveal novel therapeutic targets,” said Professor Ross Fitzgerald, Group Leader at The Roslin Institute.

Why are young plants more vulnerable to disease?

Fighting disease at a young age often comes at a steep cost to plants' growth and future...

Liquid catalyst could transform chemical manufacturing

A major breakthrough in liquid catalysis is transforming how essential products are made, making...

How light helps plants survive in harsh environments

Researchers from National Taiwan University have uncovered how light stabilises a key...