Researchers rewire stem cells to fight arthritis

US researchers have rewired mouse stem cells’ genetic circuits to produce an anti-inflammatory arthritis drug when the cells encounter inflammation. The technique eventually could act as a vaccine for arthritis and other chronic conditions.

A team of researchers led by Farshid Guilak, PhD, at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, initially worked with skin cells taken from the tails of mice and converted those cells into stem cells. Then, using the gene-editing tool CRISPR in cells grown in culture, they removed a key gene in the inflammatory process and replaced it with a gene that releases a biologic drug that combats inflammation.

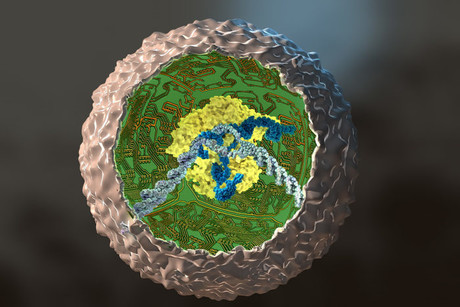

Such stem cells, known as SMART cells (Stem cells Modified for Autonomous Regenerative Therapy), develop into cartilage cells that produce a biologic anti-inflammatory drug that, ideally, will replace arthritic cartilage and simultaneously protect joints and other tissues from damage that occurs with chronic inflammation.

The cells were developed at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Shriners Hospitals for Children-St. Louis, in collaboration with investigators at Duke University and Cytex Therapeutics Inc., both in Durham, N.C.

Many current drugs used to treat arthritis — including Enbrel, Humira and Remicade — attack an inflammation-promoting molecule called tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha). But the problem with these drugs is that they are given systemically rather than targeted to joints. As a result, they interfere with the immune system throughout the body and can make patients susceptible to side effects such as infections.

“We want to use our gene-editing technology as a way to deliver targeted therapy in response to localised inflammation in a joint, as opposed to current drug therapies that can interfere with the inflammatory response through the entire body,” said Farshid Guilak, PhD, the paper’s senior author and a professor of orthopedic surgery at Washington University School of Medicine. “If this strategy proves to be successful, the engineered cells only would block inflammation when inflammatory signals are released, such as during an arthritic flare in that joint.”

As part of the study, Guilak and his colleagues grew mouse stem cells in a test tube and then used CRISPR technology to replace a critical mediator of inflammation with a TNF-alpha inhibitor.

“Exploiting tools from synthetic biology, we found we could recode the program that stem cells use to orchestrate their response to inflammation,” said Jonathan Brunger, PhD, the paper’s first author and a postdoctoral fellow in cellular and molecular pharmacology at the University of California, San Francisco.

Over the course of a few days, the team directed the modified stem cells to grow into cartilage cells and produce cartilage tissue. Further experiments by the team showed that the engineered cartilage was protected from inflammation.

“We hijacked an inflammatory pathway to create cells that produced a protective drug,” Brunger said.

The researchers also encoded the stem/cartilage cells with genes that made the cells light up when responding to inflammation, so the scientists easily could determine when the cells were responding. Recently, Guilak’s team has begun testing the engineered stem cells in mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases.

If the work can be replicated in animals and then developed into a clinical therapy, the engineered cells or cartilage grown from stem cells would respond to inflammation by releasing a biologic drug — the TNF-alpha inhibitor — that would protect the synthetic cartilage cells that Guilak’s team created and the natural cartilage cells in specific joints.

“When these cells see TNF-alpha, they rapidly activate a therapy that reduces inflammation,” Guilak explained. “We believe this strategy also may work for other systems that depend on a feedback loop. In diabetes, for example, it’s possible we could make stem cells that would sense glucose and turn on insulin in response. We are using pluripotent stem cells, so we can make them into any cell type, and with CRISPR, we can remove or insert genes that have the potential to treat many types of disorders.”

With an eye towards further applications of this approach, Brunger added, “The ability to build living tissues from ‘smart’ stem cells that precisely respond to their environment opens up exciting possibilities for investigation in regenerative medicine.”

Breakthrough blood test for endometriosis developed

Scientists identified 10 protein biomarkers, or 'fingerprints' in the blood, that can be...

A simple finger prick can be used to diagnose Alzheimer's

A new study is paving the way for a more accessible method of Alzheimer's testing, requiring...

Experimental blood test detects early-stage pancreatic cancer

The new test works by detecting two sugars — CA199.STRA and CA19-9 — that are...