From little grants big labs grow

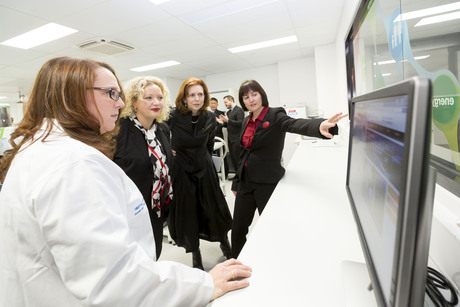

In August this year, the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (MIPS) officially opened its new laboratory — an analytical hub that is intended to bring together researchers from across Victoria. It was the culmination of a series of events that began way back in 2006, explained associate professor and lab director Michelle McIntosh.

The idea

“When I first started at Monash, in about October 2006, one of the first things that I did was sit down and go through the websites of all the different philanthropic funding organisations that fund biomedical research,” Associate Professor McIntosh said. “I’d written a research proposal asking for funding for equipment to help me establish a lab that would allow me to look at drug delivery via the lungs. That grant was submitted early in 2007.”

A few months later, Associate Professor McIntosh received a grant for $50,000 from the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust (HMSTrust), which funds projects that seek to benefit the people of Victoria. This enabled her, through MIPS, to purchase an analytical separation system.

“It was kind of the first piece of equipment that allowed me to set up my own lab,” Associate Professor McIntosh said.

Fast-forward to a meeting between Associate Professor McIntosh and her colleagues, where they were looking to come up with a suitable Master’s project for a student with an interest in analytical chemistry and bioequivalence. Their idea was to formulate oxytocin — a hormone which is typically injected into new mothers to treat postpartum haemorrhage — to be absorbed via the lungs.

“In developed countries, oxytocin is the gold standard therapy, so deaths from postpartum bleeding are very rare,” Associate Professor McIntosh said. “Yet women in developing countries don’t have access to this life-saving drug because it requires refrigeration and trained staff to administer it.”

Associate Professor McIntosh sought to develop an aerosol delivery system for oxytocin that can be inhaled by patients from a simple, disposable device immediately after childbirth. The analytical equipment purchased with her HMSTrust grant would enable the project to get underway, but this was just the beginning.

“We had support from the AusAID scholarship for the student who was doing the Master’s degree,” Associate Professor McIntosh said. “We also managed to get a small grant from the ANZ Trustees, for $19,000, and the grant for the equipment to allow us to do the work from Helen Macpherson Smith. And then the next grant we got was a Grant Challenges Explorations grant of $100,000 from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and that was sort of at the point that we really recognised, globally, what a need there was.

“And then funding again the following year from Saving Lives at Birth with $250,000, and it was that grant where we were also given an award for being the technology innovation most likely to transform maternal and neonatal health. That was probably the pivotal moment for us in thinking, ‘Okay, this project’s really important.’”

Things came to a head in September 2014, when an international group of funders announced that they would partner with MIPS to develop the new medicine. The McCall MacBain Foundation, Grand Challenges Canada and the Planet Wheeler Foundation would provide US$2.7 million funding to leverage a GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) cash and in-kind contribution to ultimately deliver a US$16.6 million early-phase development program. The resulting technology will be licensed to GSK, which will be conducting a phase 1 clinical trial of the technology in conjunction with MIPS in the very near future.

The lab

With the inhaled oxytocin project set to save countless lives in developing countries, MIPS wanted to give other Victorian researchers a chance to develop their skills and projects. With the assistance of $1.2 million from the HMSTrust, $1.1 million of in-kind contributions from PerkinElmer and Shimadzu and a further $350,000 from the McCall MacBain Foundation, the HMSTrust Laboratory was born.

“What we wanted to do was set up a real analytical hub for other researchers from across Victoria — or Australia, if there was a desire — to come in, access something for a short period of time or on a routine basis, and get some training and advice,” Associate Professor McIntosh said.

Supporting capacity building, skills growth and education development, the facility’s training capabilities will enable the development of the next generation of scientists. As explained by Associate Professor McIntosh, “It makes less sense for individual research groups to have their own capabilities in their own labs that are only used by a few people, rather than centralising these capabilities and making sure that they’re available to as many people as possible and used as much as possible.

“We’re not charging rates that will preclude people from accessing the instruments.”

Not only has the facility brought together various research institutions and organisations, but also two instrument suppliers who would normally be competitors.

“PerkinElmer and Shimadzu both operate in the same space in terms of instruments for the pharmaceutical industry, but we’ve had discussions and found a way that we can all work together with the view of ensuring maximum use of instrumentation,” Associate Professor McIntosh said. As a result, equipment from both companies is available for use inside the lab.

“Instrument support companies don’t do drug development, but both companies see the value in what we’re doing for inhaled oxytocin, so they could be providing support for projects such as that … [and] there are other projects going on that the companies are keen to see progress,” Associate Professor McIntosh explained.

Associate Professor McIntosh anticipates the HMSTrust Laboratory will be beneficial to both pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical industries, including foods and beverages, dairy and petrochemicals. Should any visitors to the facility go on to have half as much success as the inhaled oxytocin team, the lab is sure to have a significant and ongoing impact on global health.

AI-designed DNA switches flip genes on and off

The work creates the opportunity to turn the expression of a gene up or down in just one tissue...

Drug delays tumour growth in models of children's liver cancer

A new drug has been shown to delay the growth of tumours and improve survival in hepatoblastoma,...

Ancient DNA rewrites the stories of those preserved at Pompeii

Researchers have used ancient DNA to challenge long-held assumptions about the inhabitants of...