Invisible film and damage response: eye-opening research into the cornea

Two groups of Australian scientists have announced separate studies into the cornea, bringing hope to the millions of people suffering from visual impairment worldwide.

The cornea — the transparent layer at the front of the eye — must remain thin in order to stay healthy. A layer of specialised cells (corneal endothelial cells) on its inner surface maintains the cornea’s moistness by ‘pumping’ water out of it. However, trauma, disease and ageing can reduce the numbers of these cells, eventually causing the cornea to become swollen and cloudy.

Researchers at Sydney’s Centenary Institute, led by Dr Guy Lyons, have identified that the damaged cells in the centre of the cornea are shed into the tear fluid. New cells are then made at the edge of the cornea and later migrate to the centre to replace the shed cells.

The study has shown that the mechanism that drives this migration to the centre is very simple, not requiring interactions with other cells in the eye. Dr Lyons said this research, published in the journal Nature Communications, could assist in designing new treatments to repair eye damage that the body would otherwise be unable to.

“If we can understand what makes the healthy cells migrate and proliferate to replenish the damaged tissue, we might be able to design treatments to repair the damage,” said Dr Lyons.

As corneal endothelial cells cannot regenerate themselves, the only treatment currently available requires donor corneas to be transplanted into the patient’s eyes. But the transplant process damages some corneal endothelial cells, and the donor cornea may still be rejected by the patient’s immune system.

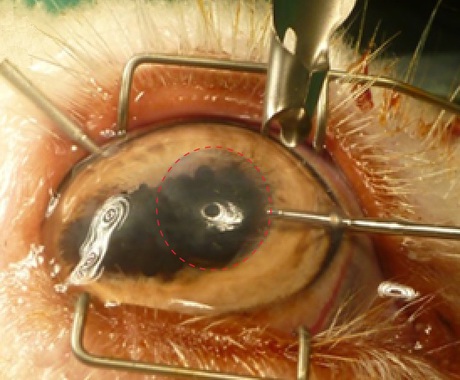

Now, a research team led by the University of Melbourne has come up with an alternative solution — growing corneal cells on a layer of synthetic film that can be implanted in the eye.

“The hydrogel film we have developed allows us to grow a layer of corneal cells in the laboratory,” said researcher Berkay Ozcelik. “Then, we can implant that film on the inner surface of a patient’s cornea, within the eye, via a very small incision.”

Ozcelik developed the synthetic film at the University of Melbourne’s Polymer Science Group, working with the Centre for Eye Research Australia. Thinner than a human hair (50 µm), the film is perfectly transparent when implanted.

Once in place, the new cells restore the cornea’s vital water-pumping activity, so that the cornea once more becomes transparent. The film completely biodegrades within two months and causes no adverse immune reactions.

“We believe that our new treatment performs better than a donated cornea, and we hope to eventually use the patient’s own cells, reducing the risk of rejection,” said Ozcelik.

“Further trials are required, but we hope to see the treatment trialled in patients next year.”

Real-time sequencing helps combat golden staph infections

Tracking bacterial changes during serious Staphylococcus aureus (golden staph) infection...

Single-cell sequencing capability boosted in South Australia

The South Australian Genomics Centre has become the first certified service provider in...

Biomaterial helps to reverse aging in the heart

The discovery could open the door to therapies that rejuvenate the heart by changing its cellular...