The human skull evolved as our ancestors learned to walk

Researchers have confirmed that the evolution of bipedalism in fossil humans can be detected using a key feature of the skull — a claim that had previously been contested.

Compared with other primates, the large hole at the base of the human skull where the spinal cord passes through, known as the foramen magnum, is shifted forward. While many scientists generally attribute this shift to the evolution of bipedalism and the need to balance the head directly atop the spine, others have been critical of the proposed link.

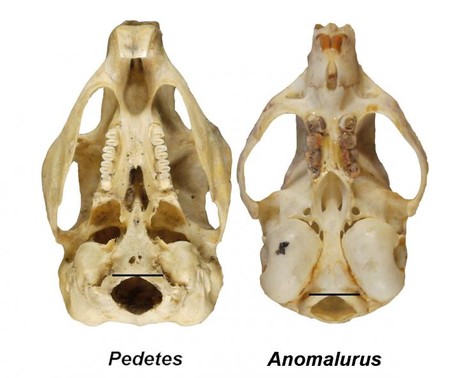

Now, two US anthropologists have shown that a forward-shifted foramen magnum is found not just in humans and their bipedal fossil relatives, but is a shared feature of bipedal mammals more generally. Gabrielle Russo from Stony Brook University and Chris Kirk from The University of Texas at Austin used new methods to quantify aspects of foramen magnum anatomy and sampling the largest number of mammal species to date.

“This question of how bipedalism influences skull anatomy keeps coming up partly because it’s difficult to test the various hypotheses if you only focus on primates,” Kirk said. “However, when you look at the full range of diversity across mammals, the evidence is compelling that bipedalism and a forward-shifted foramen magnum go hand in hand.”

To make their case, Russo and Kirk compared the position and orientation of the foramen magnum in 77 mammal species including marsupials, rodents and primates. Their findings, published in the Journal of Human Evolution, indicate that bipedal mammals such as humans, kangaroos, springhares and jerboas have a more forward-positioned foramen magnum than their quadrupedal close relatives.

“We’ve now shown that the foramen magnum is forward-shifted across multiple bipedal mammalian clades using multiple metrics from the skull, which I think is convincing evidence that we’re capturing a real phenomenon,” Russo said.

By validating this connection, Russo and Kirk believe they have provided another tool for researchers to determine whether a fossil hominid walked upright on two feet like humans or on four limbs like modern great apes. Additionally, their study identifies specific measurements that can be applied to future research to map out the evolution of bipedalism.

“Other researchers should feel confident in making use of our data to interpret the human fossil record,” said Russo.

Repurposed drugs show promise in heart muscle regeneration

The FDA-approved medications, when given in combination, target two proteins that regulate the...

A pre-emptive approach to treating leukaemia relapse

The monitoring of measurable residual disease (MRD), medication and low-dose chemotherapy is...

Long COVID abnormalities appear to resolve over time

Researchers at UNSW's Kirby Institute have shown that biomarkers in long COVID patients have...