Mythbusting with microfossils

There’s no doubt that fossils provide an important window into the past, but just how much do we know about these traces of ancient life? Researchers from the Universities of Oxford, Bristol and Western Australia decided to find some answers, collaborating together on a project billions of years in the making.

Arguably one of the biggest milestones in the history of palaeontology came in 1993, when US scientist Bill Schopf described micrometre-long, carbon-rich filaments within 3.46 billion-year-old Apex chert (microcrystalline quartz) from the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Schopf likened the filaments to certain forms of bacteria, leading to their distinction as the earliest evidence for life on Earth.

But the microfossils soon came under scrutiny, with a team led by late Oxford University Professor Martin Brasier revealing that the host rock was not part of a simple sedimentary unit but actually came from a complex, high-temperature hydrothermal vein, with evidence for multiple episodes of subsurface fluid flow over a long time. In 2002, the team claimed that the ‘microfossils’ were in fact pseudofossils formed by the redistribution of carbon around mineral grains during these hydrothermal events.

It is only recently that scientific instrumentation has reached the level of resolution needed to map the chemical composition and morphology of the microfossils at the submicrometre scale. This led to the use of a transmission electron microscope (TEM), based at the University of Western Australia’s (UWA) Centre for Microscopy, Characterisation and Analysis, to build up nanoscale maps of the microfossils’ size, shape, mineral chemistry and distribution of carbon.

UWA researcher Dr David Wacey explained that the team studied a range of microfossils as part of the project - each of which featured “coherent, rounded envelopes of carbon having dimensions consistent with their origin from cell walls and sheaths”. But when it came to the Apex microfossils, they found “a complex, incoherent spikey morphology, evidently formed by filaments of clay crystals coated with iron and carbon”, he said.

It was determined that the Apex microfossils comprised stacks of plate-like clay minerals arranged into branched and tapered worm-like chains. Carbon was then absorbed onto the edges of these minerals during the circulation of hydrothermal fluids, giving a false impression of carbon-rich, cell-like walls. The revelation has been published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

“Mapping plus focused ion beam milling combined with transmission electron microscopy data demonstrate that microfossil-like taxa, including species of Archaeoscillatoriopsis and Primaevifilum, are pseudofossils formed from vermiform phyllosilicate grains during hydrothermal alteration events,” the authors stated.

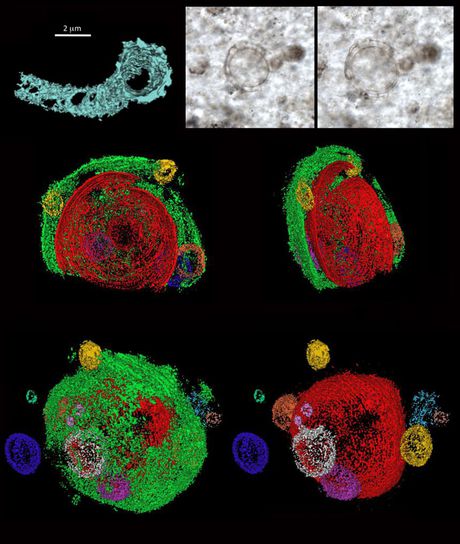

But it’s not all bad news for fossil enthusiasts - in the same journal, the team described their use of modern analytical techniques to examine genuine microfossils taken from Gunflint chert in Northwestern Ontario, Canada. The 1.88 billion-year-old chert contains a microbe called Eosphaera tyleri, and is described by Oxford University researcher Dr Jonathan Antcliffe as “one of the most incredible fossils”.

Originally discovered by Barghoorn and Tyler in 1965, the microbe is described by the researchers as having “a complex sphere-within-sphere construction, ~28-32 μm in diameter, with a thicker walled inner sphere enclosed within a thinner walled outer sphere. Each sphere is separated by a regular intervallar space containing from 0 to 15 small tubercle-like spheroids without regular arrangement.

“This construction makes Eosphaera tyleri among the most morphologically complex fossils yet known,” the authors said. Using 3D nanoscale reconstructions, enabled by focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM), the researchers discovered features of the microfossils “hitherto unmatched in any crown-group microbe”.

“The remarkable features of Eosphaera raise questions about the lack of comparable forms in the living microbial world,” the authors noted, with the Gunflint chert fossils having preserved life at a time when complex cells were just starting to emerge. Dr Antcliffe hypothesised, “It is likely that Eosphaera is somehow related to modern cyanobacteria, but at a time before even eukaryotic algae evolved.

“There would have been no competition between bacteria and algae, so bacteria were freer to explore different morphologies that would later come to be occupied by organisms with more complex eukaryotic cells,” he explained. “Life was experimenting for the very first time with how to get large, and the fossil record tells us it was doing this in a quite unique way.”

The fossil record will continue to be updated as more theories are put forth, proven and disproven. The significance of these latest discoveries may not be immediately apparent, but they are certain to contribute to humankind’s understanding of the emergence of complex life. The researchers are particularly optimistic for the future of the field, stating that the early fossil record “has the potential to help to drive forward novel biological thinking on major evolutionary questions on Earth, and maybe beyond”.

New coeliac disease test removes need for gluten consumption

The test can detect coeliac disease with up to 90% sensitivity and 97% specificity — even...

Reptiles originated 35 million years earlier than we thought

Newly discovered fossilised footprints with long toes and claws, found in a small rock slab in...

Light pollution promotes blue-green algae growth in lakes

Artificial light at night promotes the proliferation of cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green...