Depressed brains out of sync with the world

Friday, 17 May, 2013

The brain acts as a timekeeper for each cell’s 24-hour body clock, keeping this clock in sync with the world so that it can govern our appetites, sleep, moods and more. But new research shows that the clock may be broken in the brain cells of people with depression, meaning they operate out of sync with the usual ingrained daily cycle.

Circadian patterns are 24-hour rhythms in physiology and behaviour sustained by a biological timekeeping capability. Within cells, rhythmicity is maintained by feedback loops involving a set of ‘clock genes’, along with several other genes undergoing daily variations in expression levels. Evidence suggests that disruption of circadian rhythms in humans can lead to pathological conditions including depression, metabolic syndrome and cancer.

Mood disorders represent an example of dysregulation of circadian function, with studies describing abnormal circadian rhythms in hormonal, body temperature, sleep and behavioural patterns in major depressive disorder (MDD). Patients with MDD exhibit shortening of rapid eye movement (REM) latency, increased REM density and decreases in total sleep time and efficiency. But dysregulation in the brains of MDD patients has, until now, been difficult to find and characterise.

Researchers from the University of Michigan Medical School and other institutions addressed this problem by analysing postmortem brain tissues from subjects ordered around a 24-hour cycle based on their time of death (TOD), effectively treating the data points, one for each subject, as a pseudo-time series spanning one cycle. The dataset covered 12,000 transcripts for each of six brain areas for 55 controls and 34 patients with MDD. This represents the largest transcriptome-wide resource for studying brain circadian patterns in any diurnal (day-active) species.

The researchers characterised and confirmed circadian gene expression in the control brains. Many core clock genes showed strong cyclic patterns - in fact, the top-ranked gene across all six brain regions was ARNTL (BMAL1), a central component in the clock gene machinery. The data also uncovered a staggered phase relationship between the three Period genes, with PER1 peaking soon after sunrise, PER3 during midday and PER2 in the afternoon. The strength of cyclic variation was consistent across brain regions.

But when testing moved to patients with MDD, the cyclic genes were not as strong. The top five ranked genes in controls - ARNTL (BMAL1), PER2, PER3, NR1D1 and DBP - ranked the 171st, 532nd, 10,191st, 27th and 684th respectively in patients with MDD.

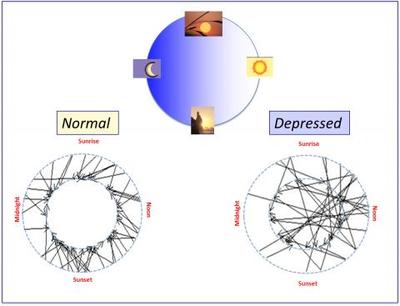

Furthermore, the researchers found a clear pattern of positive correlations among control samples with similar TODs and negative correlations between those with opposing TODs (eg, noon vs midnight) - but this pattern was much weaker between patients with MDD and controls or among MDD cases, suggesting that biological cycles for many MDD cases had fallen out of synchronisation with the solar day.

They also predicted the TOD of 60 randomly selected subjects and found that the absolute deviations of the predicted TOD from the recorded TOD were smaller for controls than for patients with MDD, further suggesting that the circadian rhythms of MDD cases were not properly synchronised.

The researchers claim the disruption of the circadian clock could be due to a number of biological causes, including the mood disorder itself, the use of antidepressant drugs or the presence of other nontherapeutic drugs taken by the subject. Examining a group of suicidal patients who had not been on antidepressants or other drugs, they found an average deviation of 3.3 h, which was larger than the average deviation for the entire control group (1.9 h) and from the average deviation of controls with a similar TOD (2.1 h). These findings suggest that circadian disruption is partially linked to the disease process itself rather than being exclusively due to the impact of drugs. However, the average deviation between predicted and recorded TOD in this group was lower than in the entire MDD group (3.9 h), suggesting that other factors may contribute.

The researchers stated that the results “provide convincing evidence that there exists a rhythmic rise and fall in the transcriptional activity of hundreds of genes in the control human brain, initiating or responding to the regulation of 24-h behavioural and hormonal cycles”, and that this rhythmicity is dysregulated across six brain regions of clinically depressed individuals. They believe the results “pave the way for the identification of novel biomarkers and treatment targets for mood disorders”.

The research was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Droplet microfluidics for single-cell analysis

Discover how droplet microfluidics is revolutionising single-cell analysis and selection in...

PCR alternative offers diagnostic testing in a handheld device

Researchers have developed a diagnostic platform that uses similar techniques to PCR, but within...

Urine test enables non-invasive bladder cancer detection

Researchers have developed a streamlined and simplified DNA-based urine test to improve early...