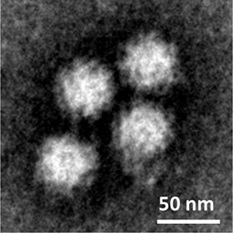

Norovirus cultured in the lab

Forty-eight years after noroviruses were first identified, US scientists have found a way to grow them in the lab. Their study, published in the journal Science, will allow researchers to explore and develop procedures to prevent and treat infection and to better understand norovirus biology.

Norovirus, also known as winter vomiting bug or the cruise ship virus, is the leading cause of illness and outbreaks from contaminated food. Unfortunately, the virus does not grow in laboratory cultures that traditionally support the growth of other viruses, such as transformed cells that are derived from cancerous tissues. In addition, noroviruses are species specific — human noroviruses only infect and cause disease in humans, and mouse noroviruses only do so in mice. Human noroviruses do not grow in mice or other small animal models typically used for research.

“People have been trying to grow norovirus in the lab for a very long time. We tried for the last 20 years,” said senior author Dr Mary Estes from the Baylor College of Medicine. “Despite all the attempts and the success of growing other viruses, it remained a mystery why noroviruses were so hard to work with.”

Dr Estes theorised that scientists had not succeeded at growing noroviruses because they didn’t have the right cell type. She showed that in patients with chronic norovirus infections, the virus could be detected in intestinal cells called enterocytes, but normal human enterocyte cells rapidly died when put into culture.

“A breakthrough came when we learned that Dr Hans Clevers’ team in the Netherlands had developed a method to make a new type of human intestinal epithelial cell culture system including enterocytes,” Dr Estes said. “These novel, multicellular human cultures, called enteroids, are made from adult intestinal stem cells from patient tissues. We anticipated that putting the virus in these non-transformed human cell cultures would let the virus grow.”

It took Dr Estes and colleagues about one year to get the human intestinal epithelial cultures growing well in the lab. After successfully testing the cultures with another human gastrointestinal virus — rotavirus — they tried with the human norovirus.

“[We] found that some strains would grow, but others wouldn’t,” said Dr Estes. “We suspected that still something was missing.”

The researchers tried to improve the growth of the viruses by adding to the cultures substances that are naturally present in the upper small intestine, the natural environment where the virus grows. Other intestinal viruses use these substances to grow inside the body.

“The human body responds to food by secreting enzymes from the pancreas and bile from the liver into the small intestine,” explained co-author Dr David Y Graham. “Pancreatic enzymes digest the large molecules and bile solubilises fats.

“Viruses that cause gastroenteritis, such as rotavirus, utilise pancreatic enzymes to trigger their replication, but these enzymes had no effect on norovirus. We asked, if pancreatic enzymes were not important, was bile a key component allowing the virus to recognise where it was and replicate?”

The answer was a big fat yes, with Dr Estes saying, “When we added bile to the cultures, norovirus strains that didn’t grow before now grew in large numbers.

“We finally solved the 48-year-old mystery. We were able to grow norovirus in cultures that mimic the intestinal environment, where the virus naturally grows, by adding bile to the cultures. Bile is critical for several important bacterial pathogens, but this is the first time it’s been shown that bile is important for the replication of human intestinal viruses.”

The researchers anticipate that these cultures will allow them to answer important questions, such as why one strain of norovirus infects one person but not another. As Dr Estes explained, “Each culture is unique and reflects the genetics of the individual from whom the culture was established.

“This allowed us to show that some cultures, like some people, are susceptible to only one or to several human norovirus strains. These cultures will allow us to determine the mechanisms that restrict replication in some people but not others.”

This is the first example where human intestinal epithelial cultures have been used to cultivate a non-cultivable agent — and Dr Estes believes that it won’t be the last.

“I predict this new culture system, changing certain conditions, will allow for the cultivation of other viruses or bacteria that we cannot grow at the moment,” she said. “If we succeed, it will help us develop effective methods to prevent and treat infection, test vaccines, interrupt transmission and better understand how these microbes infect people, respond to bodily defences and evolve.”

Blood test for chronic fatigue syndrome developed

The test addresses the need for a quick and reliable diagnostic for a complex,...

Droplet microfluidics for single-cell analysis

Discover how droplet microfluidics is revolutionising single-cell analysis and selection in...

PCR alternative offers diagnostic testing in a handheld device

Researchers have developed a diagnostic platform that uses similar techniques to PCR, but within...