Primitive hominids lived alongside humans, researchers say

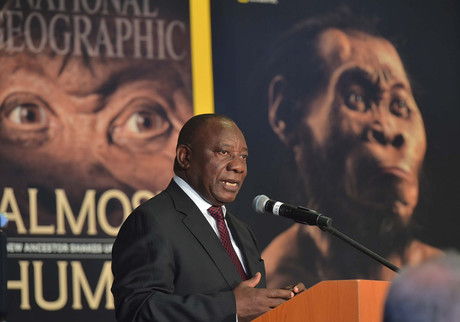

An international research team led by James Cook University (JCU) has found that primitive hominids lived in Africa at around the same time as early humans — a discovery that could have a significant impact on our knowledge of evolution.

The study began when JCU’s Professor Paul Dirks and Associate Professor Eric Roberts began analysing fossils of the hominid Homo naledi, found deep in a cave system in South Africa in 2013. They were eventually joined on the project by 19 other scientists from laboratories and institutions around the world.

The scientists learned that Homo naledi had a tiny brain, about the size of an orange, and stood about 1.5 m tall. Its teeth and skull were similar to those of the earliest known members of our genus, while the shoulders were more similar to those of apes. Its extremely curved fingers suggest climbing ability and its relatively long legs suggest it was well suited to long-distance walking. The fossils were estimated by paleoanthropologists to be 1–2 million years old, but further investigation was required.

Direct dating on the fossil remains and surrounding sediments was performed at Southern Cross University on an ESR spectrometer prototype, custom designed by Freiberg Instruments, using Uranium series dating (U-series) and electron spin resonance (ESR) dating. Professor Dirks admitted that the dating was “extremely challenging” and was eventually achieved by combining six independent methods from 10 different labs.

The result of their study, published in the journal eLife, found that this population of Homo naledi was somewhere between 236,000 and 335,000 years old — a time frame which is surprisingly recent, said Professor Dirks, given that it was previously thought that only Homo sapiens or their immediate ancestors existed in Africa at this period.

“The oldest dated fossils of Homo sapiens in Africa are around 200,000 years old,” said Professor Dirks. “And now we have a very primitive looking hominid that probably existed at the same time as them. This is the first time one of these primitive hominids has been found in association with more modern humans in Africa.”

The age for this population shows that Homo naledi may have survived for as long as two million years in Africa — well beyond what paleoanthropologists predicted to be possible, according to Professor Dirks. Critically, it is at this time that we see the rise of ‘modern human behaviour’ in southern Africa, thought to represent the origins of complex modern human activities such as burial of the dead, self-adornment and complex tools.

“The new dating puts it on the landscape at a time from which we find lots of tools in Africa in the Middle Stone Age,” said Professor Dirks. “One of the implications of the new dates is that it’s no longer automatically possible for us to assume that early Homo sapiens were making these tools.”

The researchers also revealed that they recently started work on fossils found in a recently uncovered second chamber deep in the cave system and distinct from the original site of the Homo naledi discovery. According to Dr Roberts, the second chamber is even deeper into the system than the first.

“It’s significant because one of the questions after the discovery of the first chamber was whether we had what is known as a ‘chimera’ — meaning some mythical animal composed of different parts of other animals that doesn’t really exist,” he said.

“But the new chamber shows the species is what we originally interpreted it as. We have the same morphology on a skeleton and two other partial skulls in the chamber.”

Professor Dirks said the find shows that the history of evolution is far more complicated than just a straight sequential history.

“We have many different branches on the family tree and it is only fairly recently that there is only one survivor on the landscape,” he said. “The new dating of the fossils opens up all sorts of possibilities for an interchange of tool use, cultural activities and behaviours between Homo naledi and Homo sapiens.”

Specially designed peptides can treat complex diseases

Two separate research teams have found ways to create short chains of amino acids, termed...

Exposure to aircraft noise linked to poor heart function

People who live close to airports could be at greater risk of poor heart function, increasing the...

Predicting the impact of protein mutations with simple maths

Researchers have discovered that the impact of mutations on protein stability is more predictable...